Donkey Boy

Unbound to be Broken: My 200 miles of flint, hills and harmony

- ,

- , Races

My dad, a lifelong educator, has a favorite saying whenever he takes a group of his students camping:

“There are two types of people in life, like in s’mores making, there are ‘Browners’ and there are ‘Burners.’ Burners play with the fire, while Browner’s have trust in their time.”

While that saying is predominantly about soft, goopy, pseudo plastic desserts, the debate applies perfectly to an event like Unbound. In a world full of Burners, it can pay to be a Browner.

But enough about marshmallows! Here is the story of my Unbound:

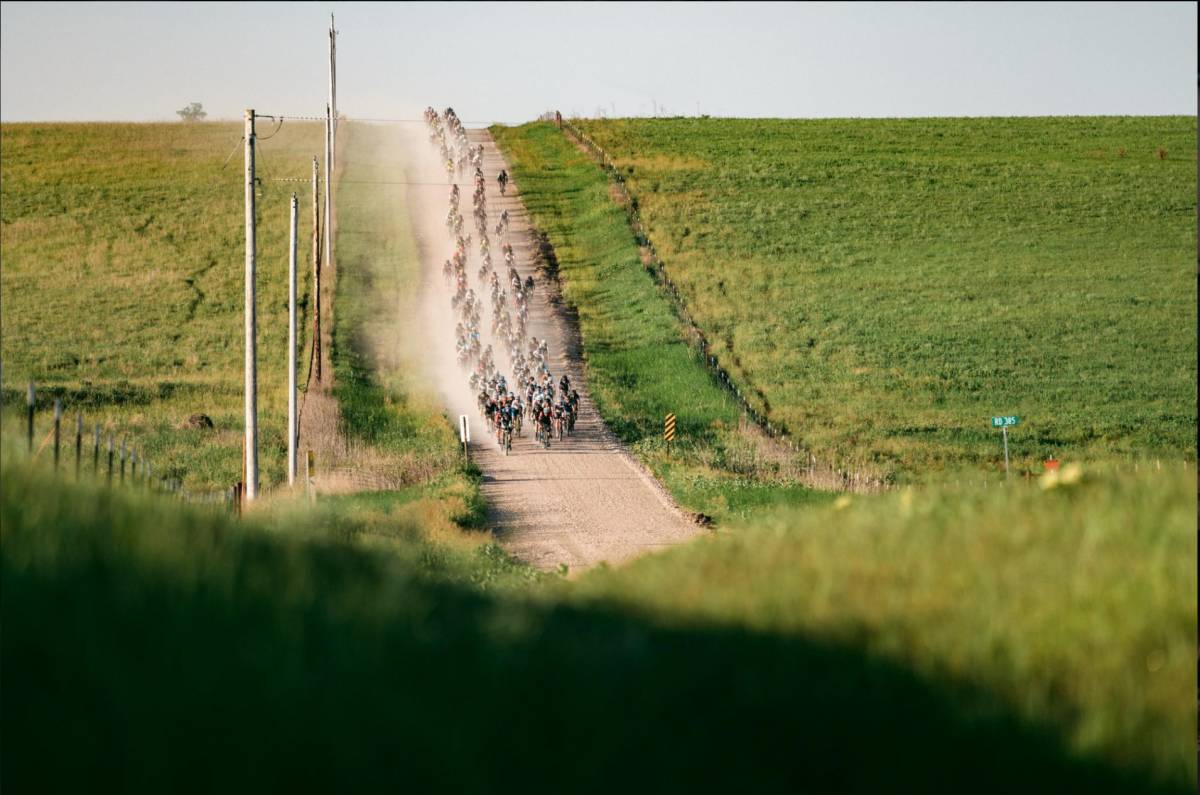

In an event like Unbound, the mystique quickly cultivates the drama. Looking back across the prairie, as a benevolent morning sun shines across the verdant fields of soupy humid mist, would be enough to paint a truly beautiful scene. Yet, that only scratches the surface of the surreal morning-scape of Unbound. Amongst those rolling pastures, rumbles what can only be described as a convulsing, slithering gallop of a thousand fantastically fit humans.

From a thousand feet up, the masses and the turbulent cloud of their might would look shockingly peaceful. However, from the ground as you pedal through the lines of rank and file of the thousand’s of tires rattling over the crushed flint, the tranquility is replaced by the sporadic flying shrapnel of three-inch stones ominously floating by tense faces, waiting for something to snap.

Then, in what feel like an instant, chaos is all that remains.

When the peloton hit the first double track, our world exploded. First it was my chain spluttering off of my chainring, and with the chain came flat number one. A chase followed, and a quick hello to @stevetheintern was followed promptly by the tragedy that is special to us who find solace in riding over small rocks in the quickest of fashions:

Pppppppapppsssssssssssssssssssssssssssssshhhhhhhhhhhhhhoooo!!!!!

Leg over the seat, plug out of the feed bag, thumb to the hole, oh that’s a big hole, plug the hole, pop the Co2 and hope to god.

I was lucky enough to complete this process, to a slower degree each time, four times as the tire remained petulantly air-free. Eventually, at mile forty, my front tire with its two holes and four plugs started to hold air and in front of me was a mere 165-miles and half the discombobulated field, in front of me.

In the next miles was a process, an excitement, at the prospects of what was ahead. Gone were the expectations that came with riding with favorites, gone were the rough and tumble that came from the masses. What remained was a lonely road of redemption in the most tangible way.

It was time for me to brown that metaphorical marshmallow.

Entering the Northern portion of the course I got to work in the heart of the Flint Hills. Here were the rambunctious parcour of big gravel, double track rollers, and gnar that I love. It was chundery, hot and windy in just the right directions. All the elements that I relished racing in, all the components that had inspired me to pour on the miles in the buildup to the race were in front of me. Meanwhile, the bad luck that was bound to come, was mentally in my rear view.

It was a shocking turn of optimism that could only come in the face of something so daunting. Up ahead I knew the Burners would push far too close to the flame. I had all the chance to Bronze my way to the promised land. With that gusto came a steady and unrelenting mindlessness to the effort, a proud and defiant return to the satisfyingly painful place of past odysseys. I quickly found a rhythm of accelerating up the hills and eating and drinking on the downs, finding dots in the distance to tether me forward.

One after another, I would pound my way across the rubble to another forlorn face against a backdrop of the rolling prairie. In the heat of the sun, I had a moment with each of these riders, whether it was a moment of weakness or a moment of strength, to see the full experience deeper. I was simultaneously a competitor and a spectator on each of their own journeys.

Of all the magic of that day, it was this dichotomy which resonated with me the most and was something that I will keep with me as I keep diving into the gravel experience. In this experiment we call mass-start, participatory driven, “pro” gravel racing all the lines are fuzzy. In the end, we are simply bodies trying to finish as fast as we can. Going through the field showed me a story of relative glory, of countless battles being waged from within and played out on this communal battlefield of elemental hardship.

Men and women, old and young (well, mostly old), finding their own motivation from the sources that surrounded them. We all had the same distance, over the same rocks, fighting the same wind and heat. It is gravel’s greatest strength, and a strength those who only dwell in their own cocoon of competition can’t see. For me, I was able to live and see it all, through the lens of clear eyes and good legs.

Slowly but surely the groups got sparse, the gaps got bigger, and the forlorn faces were fewer and farther between. It was almost an unavoidable scene of irony, becoming more alone as I climbed higher on the leaderboard. Eventually, I found a partner at mile 130. He had crashed into a ditch and was on his way forward. In our wake were the detritus of pro road and mountain bikers who had burned their way to dust. In front of us was an unknown number of people we did not know we could catch.

In the devilish Kansas wind, my partner, Barrett and I, rallied our way to check point number two where my amazing Rodeo crew was waiting. As I entered the little town, the 155 miles covered weighed on me in a silly little way. All around me I had seen broken people. For miles and miles were empty stares and emptier legs, the ambition of the start fading fast. Yet, I was elated, like I had been there before, yet I was learning something new.

My marshmallow was browning juuuust right.

With a hoot and a holler, I came screeching to a halt under our pink pirate flag whipping in the wind above and surprised faces all around me. Between cramming pickles in my mouth – with gummy worms and pringles as a chaser – my enthusiasm couldn’t be contained. I think people were shocked to see it and that only fed my fantastic fury.

I was just happy to be pedaling and had been busy thinking nothing at all except for my examinations of the people I had passed. In a way I was waiting for my inevitable downfall that still seemed so far away. That enthusiasm was much needed in the final leg.

While the start is grand, and the middle is rugged, the final of Unbound is something in between. In its moments, it is the most beautiful. In other moments, it reminds you of all the “wait, I really have to go to Kansas?” thoughts that you ask yourself as you travel the thousands of miles to and from Kansas. It’s a giver and a taker. This year it was 50-miles of head and tail wind, unrelenting until the very end, taking much more than it gave. But, as the day had seemed destined to proceed, things turned around as Edward Anderson, my good friend from Virginia, followed me out of the aid station and into our wind-swept future.

What I feared would be a long drawn-out march for home was again mollified by the recoil of the fate of the day. Instead of acting as a drag on my experience, the last fifty miles proved to be some of my strongest. Working with Eddie, or Shreddie as we call him, the wind was cut into digestible slices. Every time we turned away from the headwind, the inner Belgian in me would come out and the pace would heighten. Eventually we reeled in another rider and I opened up a gap on Eddie.

In retrospect, it was a mindless mistake. But in the moment, it was a stroke of relentless mindlessness. It is the Unbound paradox; on one hand it is a challenge of thought, while on another is an act that requires numb, dumb power. For me, the final was an expression of that numb and dumb power, as I followed my flow state back to Emporia.

Eventually, Eddie returned, and I made the right turn back onto the known turf of the morning prelude. Almost immediately, things changed. As if on a dime the hunger I had been ignoring, the dreaming I had been shunning and the speculating I had puzzling came crashing into my mind as numb concentration faded into impatient suffering. Stumbling my way back to downtown Emporia was a moment of painful clarity. Behind me, swirling around in my mind, was the experiences of the masses I had crossed. In front of me was a mass of jubilant ignorance, trying to understand the cause for our absurdity. Along the finish was me, shouting into my iPhone, at the crux of it all, finally able to fully appreciate the day that was.

After finishing, as I lay sprawled on the warm afternoon tarmac of Main St. Emporia, I found myself silent. Around me was my crew, my competitors, media and passers-by all with questions to ask. Yet, for thirty minutes I was quiet, with a dead phone and a crooked smile on my face.

Or, if you will, a perfectly bronzed marshmallow.

It’s almost shocking the amount of life you can live in 200 miles of riding; I have now learned that lesson over and over again. With Unbound, that experience – that 200-miles where every rider is suspended in their own uncomfortable reality – is so perfectly individually communal. From the buzz at the start, to the silent satisfaction of the end, the race is the perfect chance to come apart, all together. Really, that’s all we ever truly wanted.

In the end I came across the line in 11 hours and 31 minuetes, which put me in 19th place, only 25 minuetes from the 10th position.

Next up: The Oregon Trail Gravel Grinder!

No comment yet, add your voice below!