Donkey Boy

The Grandest Tour: Wheeler Peak Mountain Duathlon FKT

- ,

- , Adventures, Races, Uncategorized

See a mountain, summit a mountain.

A simple proposition, but one that can entail so many different things. Some mountains are best tackled by a lightweight road-bike, others call for a machine that is a bit burlier, and some can only be conquered by one’s own hands and feet. However, every once and a while there comes a certain summit that calls for blurring the lines between those spheres of separation.

Of the countless mountains I sampled through my sojourn out West, none provided a better canvas to blend these lines as effectively as Wheeler Peak, Nevada. Rising over the high desert in the remote reaches of the Nevada desert, Wheeler Peak is a mammoth amongst the endless barren mountains of the Great Basin. Arriving from the West, a humble visitor would have traversed hundreds of miles of the loneliest road in America to its base.

In a way, the isolation of the road and the frequency of the unremarkable mountains lulls any weary traveler into a trance. The number of small passes blend together as the twists and turns act like a sleepy roller coaster at a forgotten natural theme park. As the mile posts click by on the road to the promise of Utah, Nevada’s much lauded brother next door, the journey has an eternal, cyclical quality. Only once it has seemed as if there couldn’t possibly be anything that could break you from this interminable path forward, the towering heights of Nevada’s highest peak come careening into focus.

Unlike its cousins spread throughout the lands in my proverbial rear-view, Wheeler has an unexpected and mysterious quality to it. Smaller than the mighty Colorado Rockies, yet larger than the jagged heights of Glacier, Wheeler is not exceptional in and of itself, but is baffling in its domination of space. Matched only by the drama of the spire of the Grand Teton and the sheer significance of Rainier, Wheeler’s indignant rise out of the deserted and empty basin floors to it high altitude ring of Aspen, glaciers and tundra truly only inspires one thought:

See a mountain, summit a mountain.

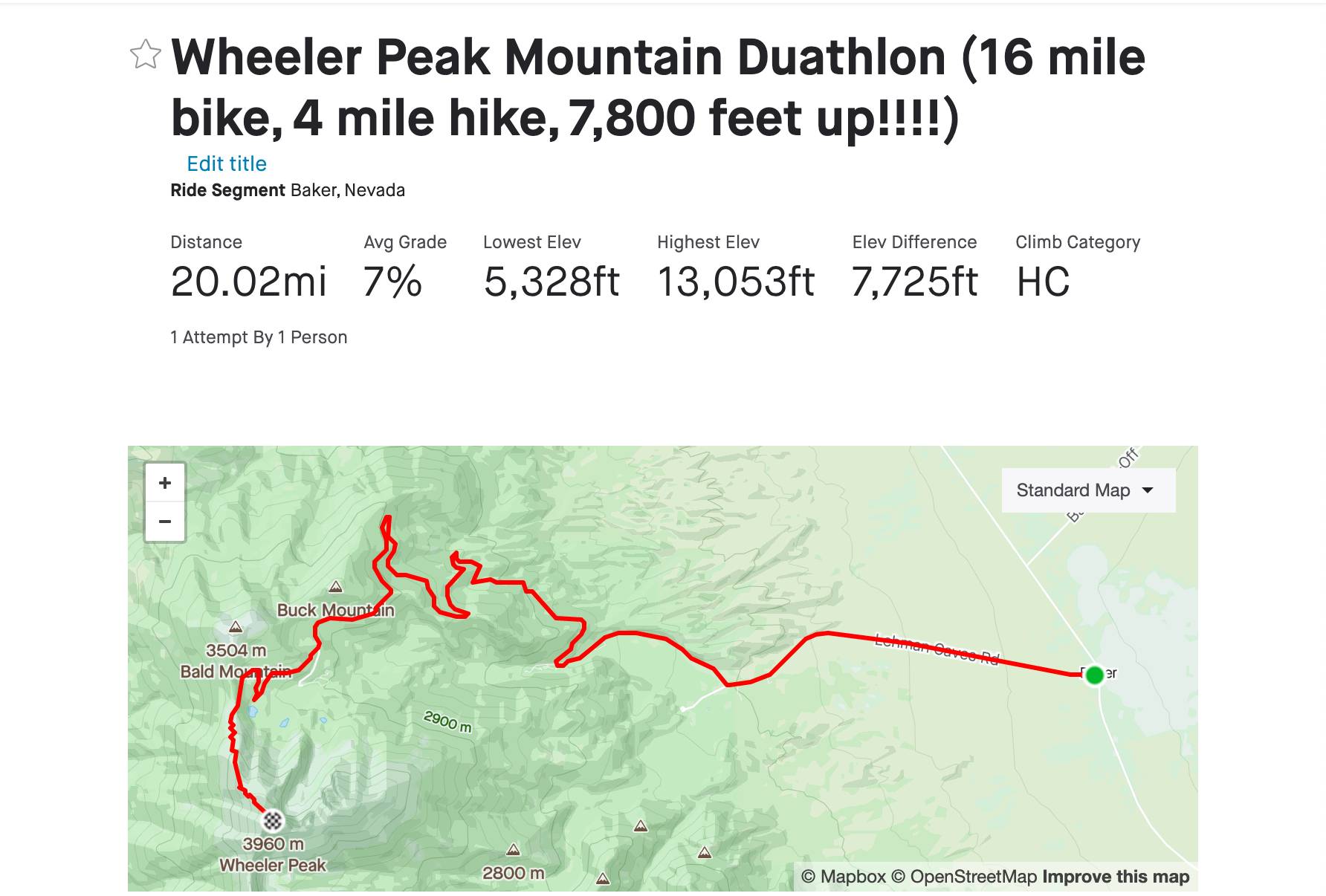

On my trip East from the promised land of pre-fire season California, that thought burrowed into my mind as the mile signs counted down the miles towards Wheeler’s home in the obscure Great Basin National Park. I had a run in with the mountain before, albeit briefly, on a trip out West in 2015. That time the 16-mile hors catégorie paved path up to the base of the final scree-filled scramble to the top was a step too far for my little legs that thought they could. Since then, the mountain has had embers flickering in the attic of my mind, hoping someday to be lit ablaze finding what I had failed to reach that long summer evening years ago. When that mountain returned to view, that fire roared between my ears. A reckoning was afoot and I would not be denied.

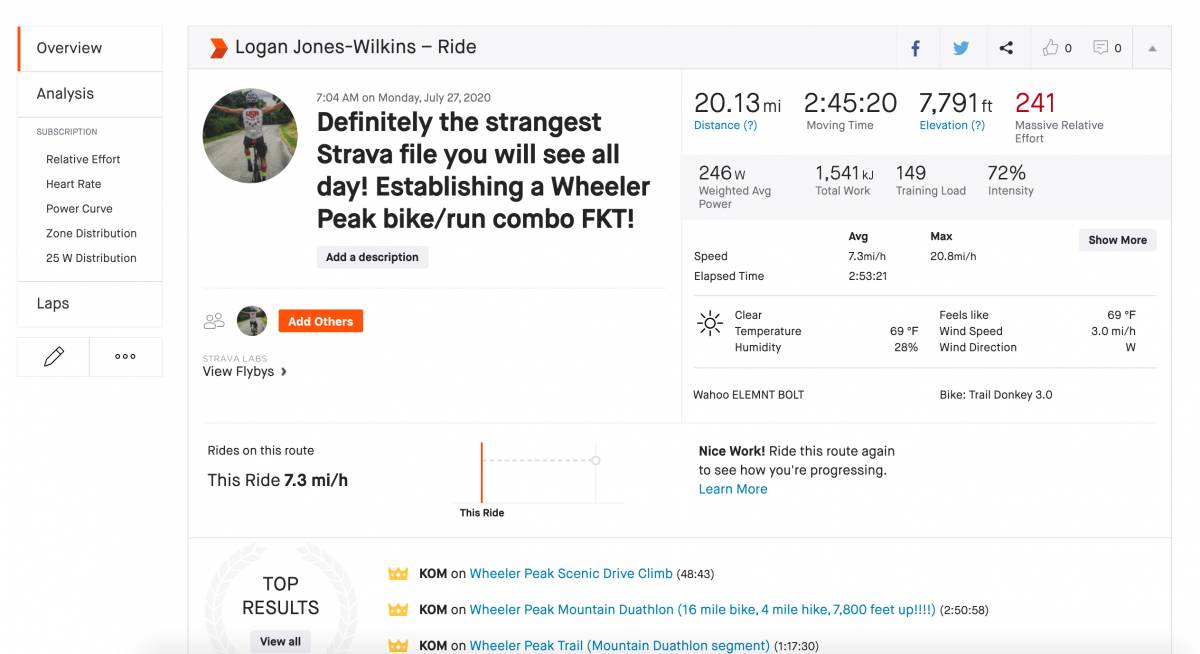

That night, as I sat in my campsite one-third the way up the mountain at a cool 7,800 feet above sea-level, I knew the 16 miles of tarmac was not enough. The mountain towering above me deserved more, I deserved more. In my fiery fascination, a plan was born to not only conquer the 16-miles of pavement, but to take on the 20-mile base to summit, bike/run/scramble that took on the mountain in all its might. In the morning instead of a simple bike ride, I would take on a 7,800 vertical feet mountain duathlon of truly epic proportions. In total 4,800 feet would be on the Donkey, while the last 4-mile, 3,000-foot push to 13,000 feet would be only on the power of my own lesser-used feet. In between would be a rapid costume change from spandex clad cyclist, to shirtless mountain man. My support was limited to two humble bottles, a couple of cosmic brownies, and a fanny pack holding my La Sportiva kicks. Rain jacket? Left in the car. Emergency gels? Too expensive. Water filter? 200 grams more than what I needed.

Preparedness is a certain attribute I tend to neglect. More on this later.

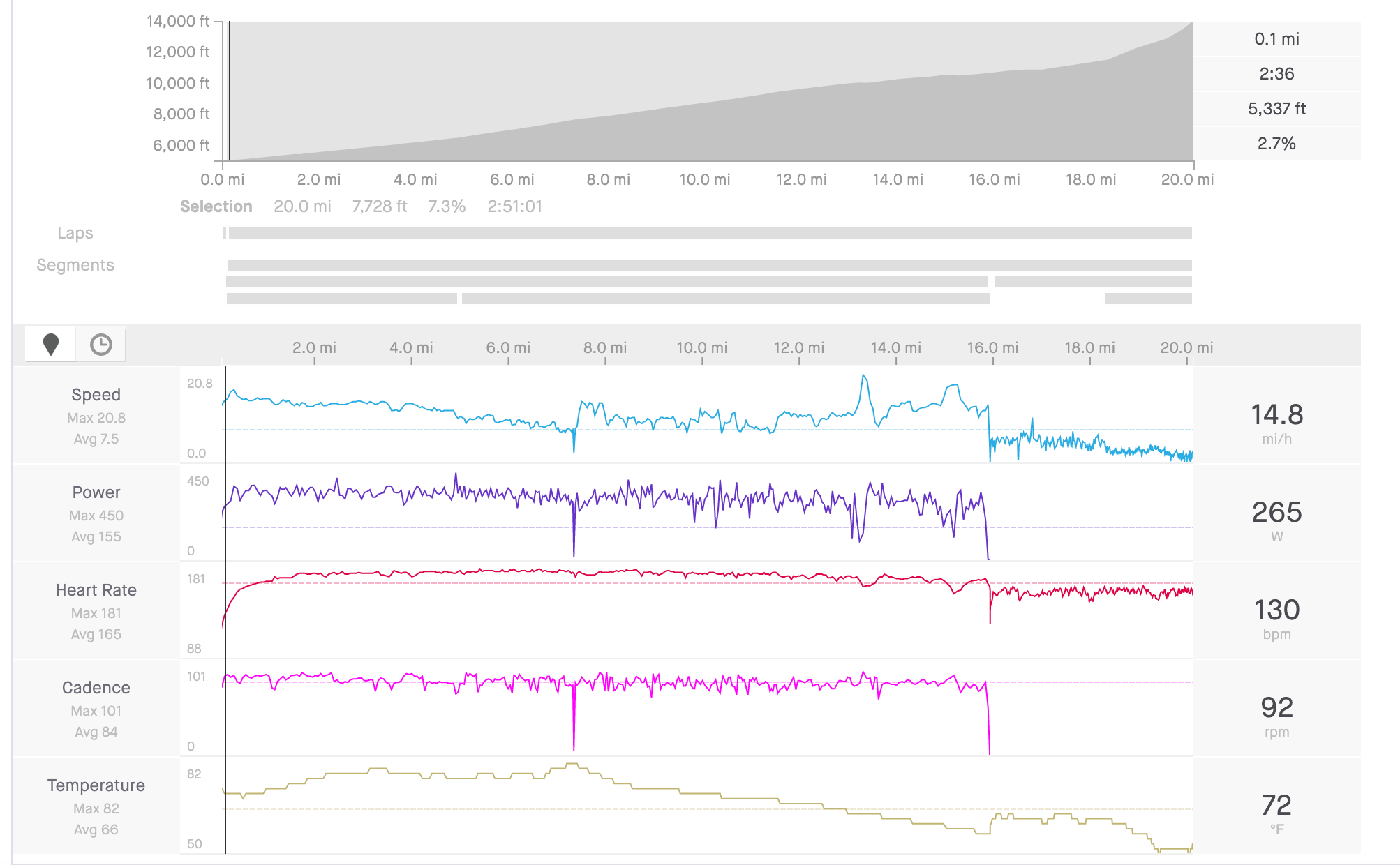

As I rolled out of the campsite at 6:40 AM, the morning sun was up and casting its kind rays on the ponderosa pines, throwing sleepy shadows on the road in front of me. The sky above was the softest of blues, yet inside my mind was a vivid picture of the pain to come, etched into the shape of the mountain which stretched up over my shoulder. Before long, I was wheeling around my bike in the one gas-station town of Baker, Nevada and taking one last longing gaze at the illuminated summit.

See a mountain, summit a mountain.

The road up Wheeler Peak is, in many ways, a perfectly concentrated snapshot of the mountain it scales. From Baker, the road rises like an arrow through the desert. Even at 7:00 AM, the rugged chip seal bounced the arid rays right into my face as I went about culling the urge I had to go irresponsibly hard. Up ahead of me, the road stretched on, unencumbered by twists and turns while holding steady at 6%. Nothing crazy, yet also a killer of the enjoyment and wonder at the task at hand. Head down, shoulders wide, heels through, repeat.

20 months (read minutes) later the road deviated from its course and the sage fell away to the sparse clumps of a ponderosa wonderland. With the poderosa and the gentle twist and turns came the teeth of the climb. Winding its way past 7,000 feet, the road followed the course of a small creek following down from the glacier sitting in the lap of the sheer face of the peak. With the babble of the brook came the 8-9% pitches of the climb, 2,000 feet from the base, yet a further 5,000 feet to climb. I really could only chuckle.

Next came the campsite with a cache of fresh bottles and a second to catch my breath. That breath didn’t last as the 8,000-foot marker was quick to follow, as the road began its serpentine quest for a reasonable path up the mountain. With each twist and turn, the expanse below grew and shifted. One turn you might catch a glimpse of Baker, growing ever fainter in the hazy of the desert sunshine. The next might instead shine the light on the road I had traversed mere minutes before. The dreadful monotony of the start was vanquished and, in its place, that same little thought popped up yet again:

See a mountain, summit a mountain.

Soon, the switchbacks leveled, and ponderosa turned to the soft shade of aspens. The clock on my computer hit an hour and twenty minutes and ahead rose the domineering presence of the peak. Even in my state of 10,000-foot suffering, pedaling through the groves of aspens etched a grin on my face I could not eradicate. Never before had an effort been so brutal, so beautiful, and so transformative. In 80 minutes, I transported myself to a different world. The natural vitality of the forest was so incredibly divergent to the hundreds of miles which surrounded it, all you could do was marvel and wonder. Maybe that’s why this day has stuck with me so much. Through the speed, the suffering, and the impending survival, the mountain reigned supreme.

I wheeled my bike to a stop at the trailhead a cool one hour and twenty-six minutes after setting off from Baker, good enough for a Strava fourth place. With a significant amount of stepping needed I had been conscious to not attack the bike as hard as I knew I could’ve in a desperate attempt to save my legs for the final. In retrospect, I don’t know how much that helped, as my legs seemed like they would’ve been jelly regardless, but these types of questions are what made this FKT so intriguing. I could go back many times and place around with pacing strategy, but at the end of the day it will always be a give and take. A lovely, chaotic, long, painful give and take.

After lacing up my running shoes and locking up the Donkey, I trotted up the trail that would take me to the promise land, and thought to myself, “ah, this rocky aspen lined trail is a picture-perfect setting for my slow demise.” All the running fitness I had built in April with was long gone, and in its place were a pair of oxygen deprived ~biker legs~ that were stumbling along the ridge to the dizzying heights of the peak above.

In a way, the run – if you can call it that – was a tail of two halves. For the first two-miles from the trail-head, the trail skirts along the shallow ridgeline of the peak, before the final two-miles and 2,000 vertical feet of boulders to the summit. Predictably, on my climb the difficulty of trying to stride well outpaced the difficulty of the scramble. I was practically begging for the steep face to the top as my quads, calves, and glutes whined at every ill-fated stride on the gradual trail up the ridge. Once I reached the rocks, each step seemed to suite my muscle structure more as I churned out an eternal tempo to the top. Periodically, my eyes would trail up and there in front of me, looking down with the might of a god, the summit called out.

See a mountain, summit a mountain.

Two hours, fifty minutes and fifty-eight minutes after setting out I hit pay dirt. Around me was a cruel and awesome landscape that seemed impossible. Thousands of feet below the desert sat, warm and yellow, while surrounding my grand pile of rock sat a cold grey tundra of endless beauty. Spinning around, one could take in a panoramic of raw nature and might that all true adventures seek. Mission accomplished.

As I sat documenting all that surrounded me, I took stock. Somehow, in my effort I had ignored the massive storm clouds that now surrounded me. The cool mist that had been my savior had become a drizzle and the temperature was seasons away from the arid summer bellow. Soon after, my phone lost its last of its reserves and the ominous roll of thunder bounced around the alpine amphitheater of the surrounding cliffs. Ah, what a good time for a jacket.

A very hurried shuffle followed as the drizzle turned to sleet and the thunder turned to lightning. My cycling jersey provided the most basic of coverings as I struggled to keep warm. Yet, even the sleet couldn’t wipe the smile off my face. In a way, I wouldn’t want it any other way. It was all part of the give and take. At the trailhead, soaked, shivering and sore, I found a grandfather and grandson with a yellow jeep and very warm hearts to help me avoid a 3,000 foot icy descent (the kid was also named Logan!) and soon I was sprawled out in my tent in most of the clothes I had, soaking in all I had just experienced.

In the days that followed, what stuck with me – and I mean burned into the fabric of my mind – was the supreme feeling of power associated with that peak. The power of weather, the power of the landscape, the power of the vegetation, the power needed to even reach the top are all astounding. It was a truly all-encompassing effort in an truly baffling place.

With this effort, I really hope that I can do more of these cross-discipline FKT’s. Mountains provide a perfect template to seek these ultimate cardio challenges. I have not been the only athlete seeking out these “mountain duathlon.” The legendary Anton Krupicka set the new low bar on Longs Peak which was awesome to see. If you are feeling antsy and need a new challenge, I urge you:

See a mountain, summit a mountain.

No comment yet, add your voice below!