Luke Hall

Renewal

- ,

- , Food for thought

Content Warning: Abandonment, Self Harm, Substance Abuse, and Bike Racing

I’ve been asked where I come from a few times. It’s a conversation-rite-of-passage in Colorado because hardly anyone is local. The answer varies depending on the context. Sometimes, my answer is Arkansas; sometimes, it’s Southeast Kansas. I’m just measuring for the judgment. January is the season of renewal and rebirth, where we start to make a new story informed by our past.

I was born in a hospital in Ft. Scott, Kansas. That hospital is now missing from the map, a casualty of the War on American Healthcare. On an early Friday morning in May, my mother, already caring for a two-year-old, faced the daunting task of raising two young boys on a waitress’s salary. As someone who struggles to look after myself, I’ve attempted to envision the anxiety she must have felt. A paternity test confirmed my father’s identity, a general contractor who struggled to find any bikes to fit his 6’10 frame. His lanky bike, a green-blue Fuji Espree from the mid-80s purchased while working in San Antonio, is cemented into my memory. Some Saturday afternoons, he would spend a few minutes pumping up his tires and dusting the frame off, and we would crawl along the road at my pace on my “mountain bike.” The total trip was hardly a mile, but in my imagination, we traveled all across town.

They shared custody for a few years, trading a tiny human between weekdays and weekends. My dad became increasingly concerned with my living situation and offered to take me full-time. Since I was born, he has been constructing a beautiful life with his then-girlfriend. He owned his business remodeling and building custom homes for people in the area as she worked towards becoming a teacher. Business ebbed and flowed, but he recognized the contrast of what he could provide vs. my other life. Sometimes, he would pick me up, and I was in dirty clothes, hungry, with mysterious cuts and scratches.

My birth mom decided that offer was the best thing for me, and I’d have to agree with her. Her life was chaotic and untenable, so she gave up all contact. Later on, my older half brother would recount tales of the numerous places they lived for brief periods and the multiple schools he attended. His narratives always carry a peculiar “through the looking glass” quality, leaving me to ponder where I might be today.

It’s amusing to reflect on my life revolving around bicycles now. I can vividly recall nearly every bike I owned while growing up. There was even a phase dedicated to BMX bikes when we moved out to the farm. During that time, my mom would take me to the local public library, and I was engrossed in reading Transworld BMX and Ride BMX. Ironically, my fascination with urban street riding persisted even while living on our dusty gravel road. One afternoon, I had my dad run me out to a bicycle graveyard nestled in the back of an old man’s farm. Although he seemed like he didn’t like the two of us there, he was happy to trade some cash for a pile of rusty chromoly frames and bent wheels. I wanted a BMX bike so badly, but I didn’t want to pay for a piece of crap that was going to break easily. I wanted to build my own piece of crap that was going to break easily. So we loaded up some of that man’s junk and made it our junk. My dad graciously granted me a corner of his giant workshop, and I tinkered.

At first, I had zero idea what I was doing. I pulled some parts from some half bikes and threaded them to another. In my memory, it took forever to assemble one whole bike, and I definitely stripped a crank arm, threading a pedal backward. Despite the parts I gathered, I still needed to purchase a chain and some tubes. The rest of those bike parts sat in the corner of the workshop, just rusting in a different place than that old man’s backyard. I could sense that it bothered my dad to have his space cluttered, yet he tolerated it for quite some time. Hopefully, none of those parts were worth anything–vintage BMX collectors are rabid animals.

I now see myself making little piles of “just in case” bike junk. Bins of old tires, tubes, bolts, and nuts occupy precious space in our tiny condo. I wonder what that old man was doing with the heaps of bike frames in his backyard. Although I presume he has passed away by now, envisioning those heaps bundled in a scrapyard, I can’t help but picture every piece of my bike-related clutter meeting a similar fate—gathered, tossed under a bulldozer, and crushed into tiny pieces.

I spent my childhood blissfully ignorant of the complexities in my family background. For my loving parents, broaching the subject of my biological mom seemed out of place and time. I don’t hold any blame against them, although I once did. I now completely sympathize with the complexities of such a conversation. When is the right time for it? Is it suitable for a 9-year-old? 10? 11? How often should it be revisited? Introducing such information could be traumatic at any stage in someone’s life.

I found out about my birth mom independently when I was 13, snooping through some documents. Mixed with teenage angst and hormones, my whole world shifted. I was angry, hurt, and could no longer trust the closest people in my life. There was no easy path forward, and at my worst moments, I resorted to self-harm. In those moments of torment, my thoughts were a whirlwind of anguish, rejection, and self-loathing. Scratching, cutting, or burning myself felt like grasping a breath of fresh air while drowning, if only for an ephemeral moment.

Similar solace also came from cross-country running. There was clarity in burning quads and gasping lungs. Emotional pain felt vague, but choosing my “suffering” meant control of the beginning and end. As it turned out, I discovered a talent for running. It became the first sport where I felt genuinely competitive, prompting me to invest more and more of myself into The Process. This marked the initial instance where I could recognize the tangible outcomes of my efforts, a realization that brought a thrilling sense of accomplishment.

Running leads me to a college in Western Kansas, where I experience a sense of being an outsider, feeling lonely, and being susceptible to excessive drinking. It’s my first taste of free rein, akin to my own Rumspringa. Unfortunately, my grades and track performance during my freshman year are lackluster at best.

That first summer of college, I hauled myself off to Estes Park to work the summer at the YMCA and altitude training. Outside my backdoor, I had trail-running access to the Rocky Mountain National Park and the Moraine Valley. I immediately noticed significant improvements in my training, culminating in winning my first half marathon. As summer drew to a close, the thought of leaving the iconic Rocky Mountains for the rolling cattle pastures of Hays, Kansas, seemed unimaginable. Consequently, I decided to stay for the winter to establish residency and qualify for in-state tuition at a Colorado school. Guided by a brilliant coach’s training plan, I diligently kept my nose to the grindstone.

In January 2007, Ryan Hall created a stir in the American running community by shattering the national half marathon record in Houston with an impressive time of 59:43. Watching the live coverage, I daydreamed about ascending to the pinnacle of the U.S. marathon scene. A few months later, fueled by ambition, I pushed myself to complete three weeks at 100 miles per week, feeling like Superman—until a stress fracture in my foot brought me crashing down. The pain was debilitating and exasperating, leaving a persistent fissure that never quite healed, flaring up with even the slightest increase in mileage.

I found myself spiraling out of control, making one poor decision after another. My identity as a runner slipped away, replaced by a somber narrative. Not only was I heavily indulging in drinking, but I also started buying cartons of filterless Lucky Strikes. Seeking a head rush? Smoke a Lucky Strike at 9,000 ft. It’s toasted!

When I turned 18, I reconnected with my birth mom, but I failed to realize I was unwittingly following the patterns ingrained in our shared genetics. She took pride in her capacity to consume a handle of vodka, and I found myself relishing similar alcoholic feats. It wasn’t easy to recognize the severity of the situation until she landed in a coma due to her failing internal organs. The doctors gave her mere days to live. I bid my goodbyes, made peace, and grew closer to my half-siblings. She was granted a second lease on life in a miraculous turn of events. I thought this might mark a significant turning point for both of us.

Her addictions stayed at bay for a few months. When she started to relapse, I began to put distance between us. I don’t think I was strong enough to see it all over again, knowing what the outcome would eventually be. We stopped talking, and a year later, her body finally succumbed to the abuse, barely in her 50s. I can still hear her raspy Virginia Slim’d voice on the telephone. There must be a German word to capture the essence of a relationship that should be familiar but is emotionally worlds away.

At 22, I found myself floundering back in my hometown, directionless and stupid. My head snaps to attention, and my eyes roll from the back of the sockets. I don’t know how long I’ve been passed out, but there are fresh-cut lines of Xanax in front of me. The slobber on my lip smears across my chin, and I scuba dive for the white powder. Looking up, I am surrounded by the hyena-like faces of my friends, cackling and repulsive. Much like them, I also want to see me on the floor, completely toasted. I don’t even care about making it home. The gallery of faces skew in the alprazolam washing machine, and the darkness encroaches on my vision.

The following years form a colossal blacked-out haze. I make my way to a larger city for bigger trouble. Sleep becomes a rare commodity, requiring the sacrifice of at least a six-pack of tallboys to tuck me into the night. Every so often, I try to go for a run, and I’m a hobbling shell, hacking up phlegm and nicotine. Going out for a run feels like a sad, pathetic grab for glory days. I might as well light another cigarette and stay up till 4AM.

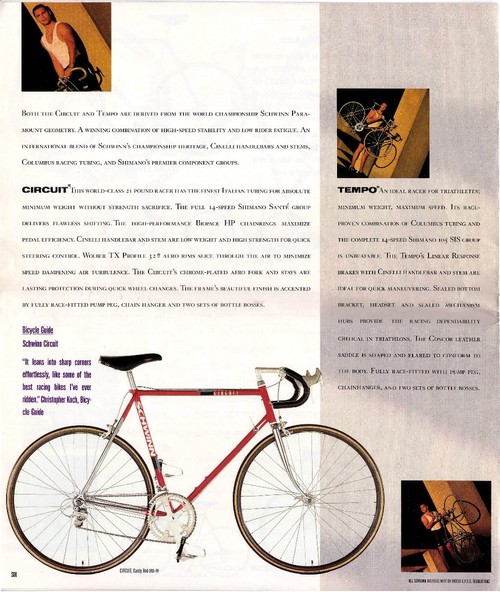

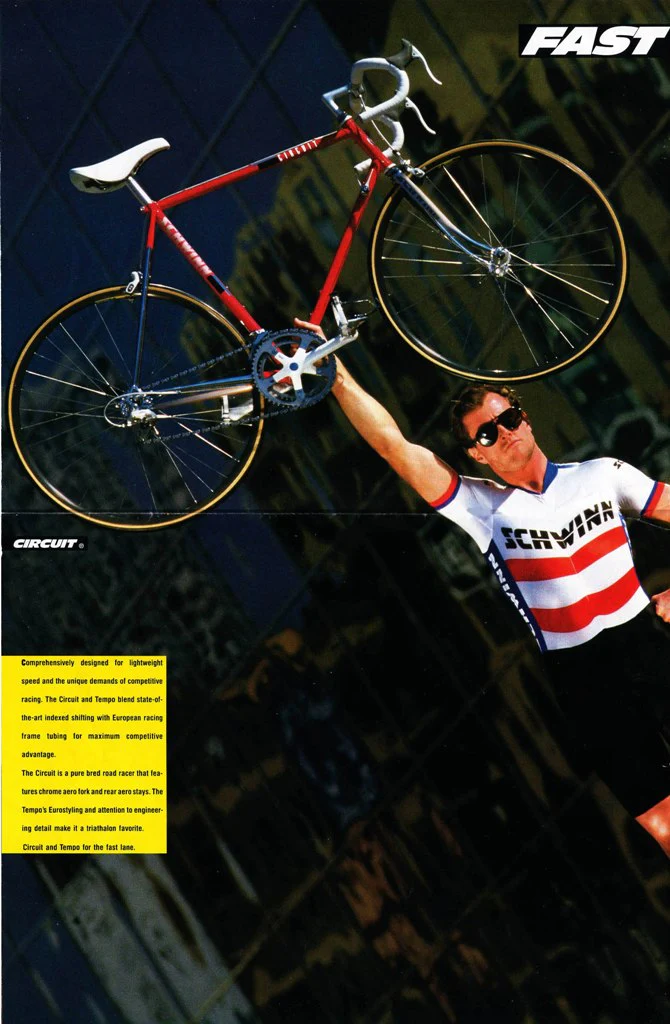

Walking down the sidewalk, I see a friend riding a bike with a group uphill at a good clip, and the image is effortless freedom. In the spring, I searched on Kansas City’s Craigslist and found Little Red Riding Hood. She is a 1988 56cm Schwinn Circuit adorned in the short-lived, white Shimano Santé. Embracing downtube shifters and clip-in pedals proved to be an awkward learning experience, but over time, I gained enough confidence to join the Brookside neighborhood group ride. The riders are kind and patient, guiding me through the nuances of courteous group riding on Thursday nights.

Juggling drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, and cycling becomes overwhelming, prompting me to cut back on the vices. My inaugural road race, the State Line Road Race in South Kansas City, is an absolute disaster. Positioned at the start among carbon fiber and lycra-clad Cat 5s, I stand out in a cotton “Hotter than Hell 100” Nike jersey from 1988 astride Little Red Riding Hood. My entire kit could have doubled as an Andy Hampsten cosplay. The rest of the peloton avoids me like the plague—either too embarrassed to be associated or scared away by my apparent lack of handling skills.

With two laps to go, I made a brave and dumb attempt at a solo break, only to be swallowed alive a lap later and promptly shit out the back. I loved every hairy second and am reconnected with a missing piece of myself.

While road racing is fulfilling and offers quick success, I foresee a dead end in the near future. Progressing from Cat 2 to Cat 1 demands a substantial investment of time and money, both of which I lack. As my enthusiasm for road racing wanes, gravel racing emerges as a rising trend, with Emporia at its epicenter—a town just 90 minutes from my hometown. In contrast to road racing, gravel feels unrefined, filled with uncertainties, and primarily dominated by individuals over 50.

Initially hesitant to embrace the discipline, there’s a certain romanticism in transitioning from growing up on a farm on a dirt road to making it the focal point of my endeavors. The grassroots essence of the sport entails standing on the same starting line as former World Tour Pros. Demonstrating your capability involves simply showing up without the need to navigate an expensive and laborious upgrade system, only to discover you can’t measure up. Suddenly, individuals with ordinary backgrounds find themselves competing with the highest echelon of American cycling. This is inspiring and revitalizes my motivation to race.

Occasionally, I find myself falling back into old habits, and much like being out of practice with cycling or running, the return is always unforgiving. I appreciate the severity of the lesson. It serves as a reminder that maintaining a dedicated practice is easier than constantly switching between two worlds.

A few days ago, a bristling black F-150 buzzed past me on the road, aggressively overtaking me just 20 yards before my turn. I’ve become adept at reading the apprehension in approaching traffic. The Jeep Wrangler in the oncoming lane veers dangerously close to the ditch, indicating that a large truck is about to pass me in a confined space. Despite my efforts to ride near the ditch to be courteous, it doesn’t seem to matter. I am 40 miles away from the Boulder Bubble, and in the driver’s eyes, I represent what he perceives as the destruction of this country: a spandex-clad exercising elitist. His truck, to me, symbolizes opposition, but I resist the urge to commit Class 3 Vehicular Manslaughter just to make a point about someone “not belonging.”

Little does he know, I grew up on roads like these and know many folks just like him. Over the next twenty minutes, I screamed everything I would say to their face and the questions I could ask to make them feel small about their rash decision. Do they realize I’m someone’s son? Are they aware that my girlfriend is waiting for me back home? The reality is, I just happened to be on the same county road as they were in a very exact moment that just required the tiniest bit of patience.

In between my endurance athlete identities, I was anywhere from intentionally suicidal to nonchalant about my own well-being. Now, I am confronted by people who disregard my safety, and I am livid, a sign I will mark as progress in my mental health. I’ve had good results in this sport over the last ten years and still see yearly growth. The feeling that I chase is no longer catharsis but an observation of craft and development. Cycling is a deterrent from succumbing to boredom vices, while adventure riding is a constant reminder that I am always capable of achieving more.

2 Comments

Incredible writing Luke. I also grew up on dirt roads and share a lot of similar feelings. Thank you for putting this into words so viscerally and delicately <3

Love this brother. Keep it up