Luke Hall

Foreign – Luke’s Traka Adventure

- ,

- , Adventures, Races, TD4

2 AM, on Sunday Morning and I’m in a Boeing at over 35,000 ft in the air. Sorry, over 11,000m in the air. When competing outside of these United States, we will use the metric system, like the rest of the civilized world. But I refuse to be some proselytizing Metric Snob just because I have been to Europe once. As soon as I cross that border, that Wahoo returns to miles and I’ll be referring to my beverages in “fluid ounces” and calling French fries by their true name, freedom fries.

I can’t sleep, and the anxiety about it keeps me awake. It is the ouroboros of insomnia, pestering, like a younger sibling on a long road trip. With the recent Boeing news frenzy and the nerves of the impending race, I’m a tangled mess of stress. I weigh the difference of dying in a ball of Boeing © ️ flames. Or perhaps careening off a cliff above the sea in Roses, Catalonia. Both scenarios are ludicrous, yet my mind knows no bounds this week. Luckily, I have on my compression socks and a 25cm (10-inch) screening of the three-hour opus, Oppenheimer. I am playing my role as a veteran international traveler but inside I am writhing. The truth is, this is my first time traveling abroad and I feel like I need a child guardian to guide me through this unfamiliar territory. Panic sets in: Did I remember to pack my battery bank? Where did I stash my passport?

For the past week, I’ve been smothered by this blanket of anxiety. I’ve been tinkering with bag setups, weighing pros and cons, and bombarding friends with stress-filled questions, each with their own varying levels of experience. The real struggle came with deciding whether to pack all my nutrition. It would mean adding a 4kg (9 pound) penalty, effectively doubling my bike’s current weight when combined with my gallon-capacity hydration bladder. Ultimately, the benefits boil down to control—control over the familiarity of my surroundings in this foreign and uncomfortable space.I can count on 100g per hour with Carbs Fuel. However, I can’t rely on urgency in a Spanish cafe when I need to grab and go, imposing my American culture of demanding service. Thus, I’ve chosen to shoulder the burden of those extra 4 kilos, viewing it as a small penance for my desire for control. At cafes I will be on the lookout for water and a carbonated sugar drink.

Everything just feels so improbable. How could this elongated aluminum Pepsi can be soaring through the sky at hundreds of kilometers per hour? How is it possible that we’re traversing the vast Atlantic Ocean in just one night? And yet, it’s equally implausible that a dream I had a decade ago about racing my bike in Europe is now on the brink of realization. But therein lies the beauty of the improbable – when it transforms into the possible. Suddenly, it’s time to recalibrate expectations and strive for new measures of success.

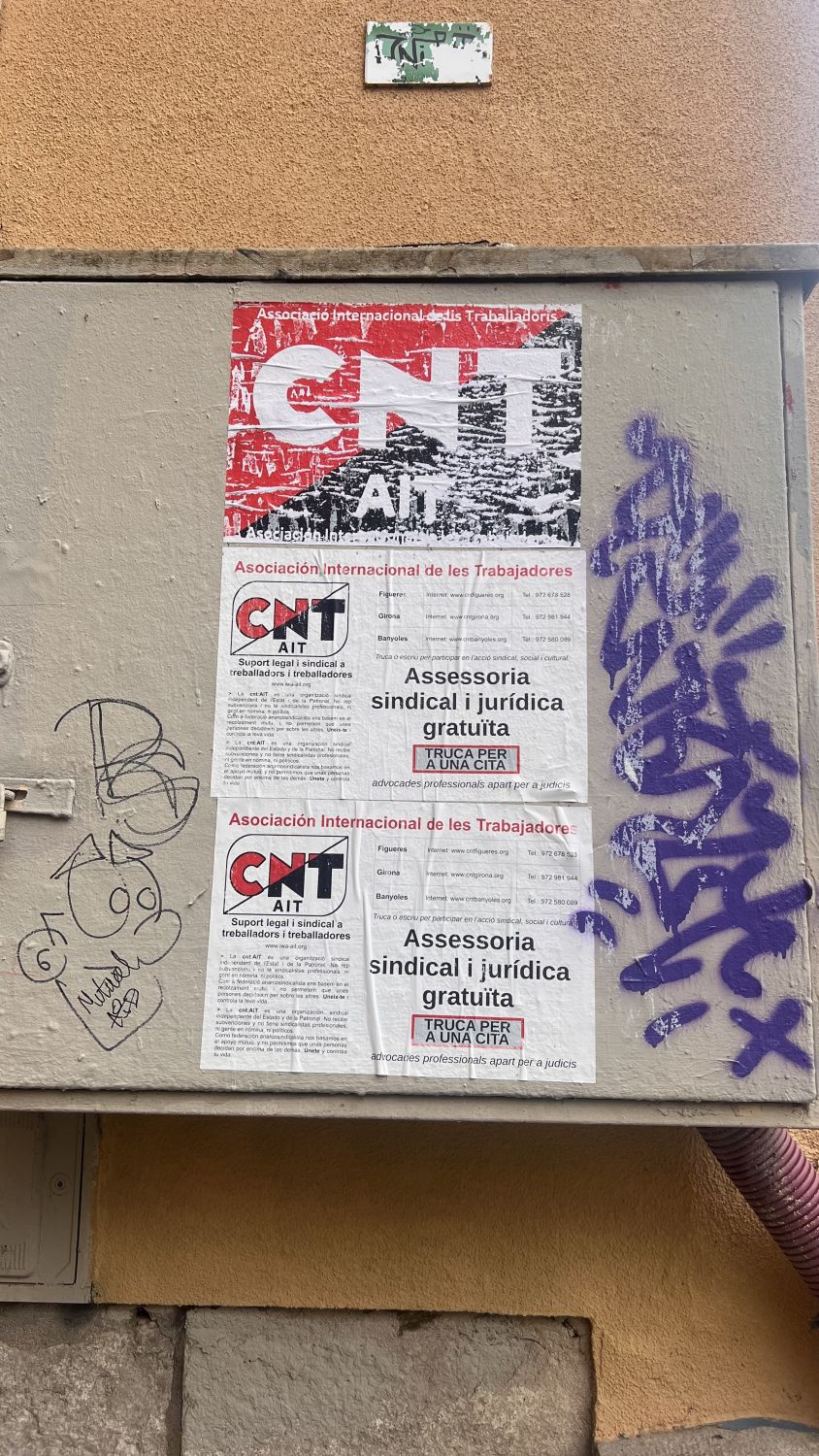

The flight unfolds seamlessly, with only a hint of turbulence – nothing remarkable. Upon touchdown in Barcelona (allow me the pretentiousness of forever pronouncing and correcting others to say “Bar-THA-lona”), the sky is draped in imposing gray clouds and sporadically spitting out fat raindrops. It’s a rocky start, yet I instantly feel more cultured. Even if I were to catch the next flight home, I could boast that I’ve been to Spain. However, as soon as I step out of the bustling airport alongside my Rodeo compatriots, my dry sarcasm takes a backseat. I stand slack-jawed, gazing at millenia-old cathedrals that seem to dot the landscape endlessly. Vibrant spray paint adorns the walls, and I can’t help but notice the scattered anarchy symbols. Yet, this isn’t merely akin to a teenager’s phase of pop-punk music. There’s a strong likelihood that their grandfather fought on the side of the Anarchists during the Spanish Civil War. The CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) in Catalonia thrives, organizing around the principles of mutual aid and worker self-management.

Barcelona has a peculiar vibe, like things are missing. For some reason, car dealerships do not have 20 meter (60ft) national flags towering over their lots like back home. I also notice a distinct lack of big dumb trucks and wonder where I’m supposed to direct my vehicular loathing. How will I be alerted of impending doom without the grumble of a diesel with a 5 inch exhaust pipe? Excuse me, 12 centimeters.

We are, as they say, a motley crew. Steve the Intern has his steadfast partner in crime, Nick. Rodeo Labs’s Wizard of Prototyping, Cade, is ready to rumble and I am thankful to be on my first Rodeo adventure. There is a nervousness on my part—will our personalities clash? Will we get tired of each other? Will I be a not fun guest? Regardless of the nerves, I was in Barcelona, on my way to Girona, Cycling Heaven.

We are all here to explore the boundaries of uncomfortableness. Emerson’s Circles is one of my favorite essays. He writes, “every action admits of being outdone. Our life is an apprenticeship to the truth, that around every circle another can be drawn; that there is no end in nature, but every end is a beginning; that there is always another dawn risen on mid-noon, and under every deep a lower deep opens.” With every step into the realms of discomfort, we are expanding our library of what we know about not only ourselves, but also our surroundings. Discomfort serves as a gateway to enlightenment.

The sensation of discomfort is what has drawn me most to the world of ultra racing. I know what 100 or 140 miles feels like. It’s not insignificant, but it is familiar. Racing for 350 miles feels like I am an early astronaut exploring the atmosphere, gaining big insights with every flight, but only able to visit this feeling infrequently.

Recovery from these efforts has to be purposeful and takes a few days. This month’s schedule is ambitious, The Traka 560k, Rule of Three 200, Unbound XL, and culminating with an attempt at the Oregon Outback FKT. There’ll be a brief respite before ramping up for a fall campaign. Every effort will take deliberate rest to recover.

My bike setup has undergone a complete transformation compared to last year’s Unbound XL. I’m hesitant to categorize these changes as ‘good’ or ‘bad’, as each presents an opportunity for growth and learning. For instance, instead of mysterious vacuum sealed bags of white powder, I’m carrying 45 gels. Don’t yuck my yum. Additionally, rather than juggling two 1-liter bottles and a 2-liter hydration pack, I’ve streamlined to just a single 3.75-liter hydration pack nestled snugly in the full frame bag from Class 4 Designs. I’ve doubled my top tube carrying capacity and added Silca’s rear Grinta bag, a tidy little seat bag made for short hauls like The Traka. This compact seat bag will accommodate 30 gels, a heavier jacket and gloves, and my lights. What I appreciate most is the balanced weight distribution on the bike. The water is positioned near the seat tube/bottom bracket, while the gels are stored off the seat. Ditching the hydration pack from my back has truly revolutionized my setup.

Initially, I hadn’t intended to pack extra clothes. However, the weather forecast shifted unexpectedly, dropping from a high of 21 degrees Celsius (70F) to 15 degrees with drizzle. Given that our route climbs up into the mountains at an elevation of 2100m (7000ft), anything is possible in terms of weather up there. My strategy is to tackle the major climbs aggressively during the first half of the 560-kilometer (350-mile) ride, aiming to descend to lower elevations where it’s cooler at night. However, adverse weather conditions could potentially throw a wrench into that plan, forcing us to contend with snow, mud, or slick, slow hike-a-bike sections.

I’m feeling overwhelmed. My mind is racing, darting from one thought to another. Sometimes, I wish I could just let go and embody the same grit as the early pioneers of Le Tour. They conquered unfamiliar snowy, dirt roads, risking their lives for glory, as immortalized in the yellow pages of L’Equipe newspaper. They did it all with nothing but simple wool for protection and rudimentary gearing. It also seems improbable.

As much as I want to soak in my experience of Girona, I am impatient to be out on that course. I want to be problem solving, eating my elephant one kilometer at a time. It feels easier to be in motion than to endure the anticipation and the waiting.

My flight into Barcelona is 80 minutes late, a fitting start to a Spanish cycling holiday. Our cab driver stuffs four bike bags into the back of his van and assures us of an authentic Catalan dining experience. Not any of this airport food nonsense for us. We arrive at a hostel/restaurant and sneak to the back for tapas. Emerging from behind the bar, the small plates offer a delightful array—pickled cauliflower, bread & tomatoes, chorizo, fried calamari, miniature octopus, and tripe. Consider us culturally submerged.

The taxi journey stretches over an hour and a half, accompanied by a persistent drizzle, before dropping us off on the narrow street where our week-long apartment is located. Primeval cobblestones snake their way upwards, while rainwater trickles down. Our temporary abode is accessible via a narrow two-story stairwell, offering a balcony with views over the bustling tourist alleyway below. This neighborhood is renowned for its ancient architecture and cathedrals, as well as being a filming location for a famous scene in Game of Thrones: Cersei’s walk of shame. The walkways are alive with people from diverse corners of the globe, all wanting a glimpse of the location of the pivotal scene.

The rain shows no signs of relenting. Since it began, the area has amassed 22 liters. To be honest, I’m not sure what to make of that figure—I’m accustomed to measuring accumulation in inches, but it seems excessive. Despite being in a purported drought, the Girona I’m familiar with is now submerged in puddles. The forecast for the upcoming days doesn’t offer much respite; it looks like we’re in for more of the same. This could turn out to be quite miserable.

Even after a decade, I’m still discovering new aspects of myself as a racer. I once thought I detested racing in unfavorable weather. Naturally, nobody relishes competing in inclement conditions, but I’ve come to realize that I can actually thrive in adverse weather. I grit my teeth and remind myself that I’m here to race against the best in Europe, regardless of the conditions.

The day before the race, there’s a course adjustment, and the start was postponed for a day due to snow in the Pyrenees and incoming storms. The new course involves less climbing and covers 20 fewer kilometers, but it includes a loop through the central farmlands, circling close to Girona before heading to the coast. This alleviates my concerns about the weight I’m carrying, and the flatter terrain aligns better with my power profile. With eager anticipation, the four of us await updates, constantly checking the buzzing Telegram thread for the Traka Adventure 560k. We wander the winding, cobbled streets of Girona, indulging in pastries from random shops and discovering hidden parks with views of the old town’s majestic cathedrals.

During lunch, we were greeted by the booming sounds of a May Day parade. A diverse crowd of people, spanning all ages, marched to the brisk rhythm of drums, proudly waving flags representing socialism, communism, or anarchism. We learned it was a protest against cycling tourism, yet I never felt threatened. It was evident that gentrification had led to increased living costs in Girona, fueling their discontent. However, the conundrum remained: how do we address the grievances while also acknowledging the vital role tourism plays in providing service jobs for many?

The next day, the Telegram thread erupted with chatter—the 560k race had been called off. Organizers expressed concern for our safety due to the impending storms, and rumors swirled that local authorities might struggle with emergency response. Our epic was abruptly canceled. We had just been on standby through our Girona experience. As the rain trickled down in the plaza where we received the news, a sense of damp disappointment washed over us. However, Steve swiftly proposed an alternative: why not tackle the 540km course anyway? Despite the potential snow in the Pyrenees, the four of us were seasoned enough to navigate the lower elevation route in adverse conditions. Frankly, I felt a wave of relief.. Perhaps I could actually enjoy the ride without the pressure of competition looming over me. We devised a plan to return to our home base, prepare our bikes, and set off at a jetlagged 4 am.

Setting up was stressful. I wanted to bring every option for clothes, not knowing what weather was ahead of us. Finding space for it all was yet another challenge. I hadn’t even really tested my new light setup before leaving. Nothing to it but to do it.

I tried to go to bed. I made a really earnest attempt. The ouroboros of insomnia was eating at my brain again. Eyes shut tightly. I tried to focus on my breaths. But then, a thought slipped in. What’s the time? Panic surged as I realized we had to prep in just an hour and a half. Suddenly, my bladder demanded attention. When I heard Nick stirring, I decided to get up too, half an hour earlier than planned. Nothing to it but to do it.

The four of us meandered through the first 12k on familiar surfaces we had experienced on the preride the day before. With 520k to go, we were all lulled into a deceptive sense of safety, nothing too serious but playful puddle dodging.

At 29 kilometers, the first significant climb presented itself—a concrete road adorned with traction lines, a true badge of authority. I pushed hard (too hard) and pulled away, ready to settle into my own pace. While I was relieved to not be competing, I still felt the itch and knew I needed a big ride for this training plan puzzle piece. I grappled with the weight of every decision, questioning whether I would regret carrying 45 gels or a gallon of water. Could I have lightened my load or stopped more frequently? How much of my attention was being consumed by worry?

I wanted to have a real race effort. In fact, My training plan leading up to Unbound XL needs it. However, without the usual competitive pressure, I found myself more relaxed, allowing me to make stops at supermarkets and cafes and enjoy the ride with my friends. Striking a balance between these contrasting ideals proved to be an interesting challenge, but it all worked out well in the end. Steve repeatedly outlined that I would be hammering and I jokingly referred to myself as The Scout, reporting bad surface conditions.

At the top of the second climb I stopped for a picture and pee break, when I heard voices of our crew. The remainder of the ride unfolded in a similar manner—covering some ground, being alone for hours at a time, then pausing for various reasons, before reuniting with familiar faces. Their presence provided a comforting sense of security in an otherwise unfamiliar environment.

After conquering our initial challenging climbs, we regrouped in a quaint village, 140 kilometers into our journey with 400 still ahead. Though I longed for an Iberico sandwich, I settled for Iberico-flavored Ruffles and pork rinds, craving the salt and fat to soothe my stomach after days of predominantly sweet carb-loading. As we lingered by the entrance of the small store, ominous dark clouds gathered on the horizon. Though uncertain of the severity of the impending weather, I felt confident in my preparedness. Forty kilometers later, we found ourselves battling against the elements. Ahead of the group, I sought refuge in an old barn by the roadside, accompanied only by a massive hay trailer. Thunder rumbled incessantly as hail hammered down from the sky. In my temporary sanctuary, I couldn’t help but worry about the safety of my companions, hoping they had found similar shelter.

There’s a fine line between courage and stupid, and I started to wonder what side we were really on. With one misstep, the situation could quickly escalate into something dire. Our decision to embark on a course deemed too hazardous by the event organizers might appear foolhardy if tragedy were to strike.

Location services were kind of whack, but Our Brave Leader sent an update on our text thread: emergency blankets and a small utility shed for shelter. My core temps were dropping so I also cracked my emergency blanket and waited for it to clear enough that we could rejoin.

My lack of sleep was getting to me. After being awake for over 30 hours, I was irritable. I questioned our ability to make wise choices at this moment. Are we charging ahead to prove a point? Would it be so bad to head back to Girona? I was cold, wet, physically tired, mentally exhausted, and my drivetrain sounded like it had zero left to give. What side of the line are we on?

We deliberated our options, analyzing the radar as if we were all meteorology experts, until I succumbed to peer pressure and agreed to continue. It appeared that the worst of the weather was passing by. While the others began moving forward, I hesitated, taking my time to tidy up my muddy gear. How on earth do they manage to pack those emergency blankets so small?

Resuming our journey, we pushed onward through the aftermath of the storm. At its peak, I navigated through hail thick enough to resemble snow, contemplating how much worse it would have been had I continued without seeking shelter. The roads were treacherous, coated in a slippery layer, with short inclines winding around water crossings. Arriving in the town of Cervia de Ter, we hoped to find a place to restock our supplies, but it was in the midst of a siesta—a few hours in the afternoon when much of Spain shuts down. It was disheartening to be soaked through and unable to find solace in warm food.

In our Telegram thread, reports on route conditions streamed in from pre-rides, accompanied by images depicting a long stretch of submerged path. I found myself unable to squeeze scuba gear onto my already laden bike. Initially, we had agreed to detour onto pavement if conditions became too treacherous. As it turned out, they were indeed horrendous, yet we remained on course. Trudging along slippery banks, my third step sank deep into the mud, sparking irritation and prompting thoughts of our unquestionable recklessness. My irritation reared its head and I thought about how we’re definitely on the stupid side now. The reroute was RIGHT THERE but stubbornness is ALREADY HERE. Completely drenched and growing increasingly frustrated by the sluggish conditions, I couldn’t help but question our decision.

I had hoped that the flatter terrain would be quicker, but it was proving to be only marginally faster. I couldn’t see how we could finish in decent time and possibly miss our flight. We were joined by Sebastian, a German who had started at 7am that morning. He seemed strong, after all he made up 3h half way through the route and his setup was legit—a set of luxurious Deda aerobars curving around his forearms. I decided to stick with him, and we exchanged intermittent small talk for about 60 kilometers. Sebastian mentioned that he had initially aimed to win today’s race, but now viewed it as valuable preparation for Unbound. Hello, my German doppelgänger. Suddenly I couldn’t care about the conditions.

As Seb and I approached the town of Figuero, I knew this would be my last chance at a decent meal before the three hour ride to Llanka. Nothing there would be open and services would be barren until probably Roses or further. I looked at my phone and found an American staple—McDonalds. I didn’t know Spanish, but I could shuffle my way through the colorful touch screen ordering kiosk, just dreaming of the incoming calories. When I turned around, there were my friends joining with the same line of thinking, now with a new face in tow from the 7am starting group.

We sat at the McDonalds stuffing our muddy mouths with Quarter Pounders and weighing our various options for getting a bit of rest and possible dry clothes:

A) push to Llanka and get a hostel

B) try to hole up in a barn for a while somewhere on the way

C) find a cheap hotel and rest for a few hours before heading out again

D) Laundromat

Steve phoned three hostels in Llanka and was only able to connect to one, receiving a curt “no.” Option B sounded iffy and dangerous, and Option D was only short term relief, so we rolled with Option C and crashed at the motel around the corner. While the bed might as well have been made of plywood, the comfort of being indoors, warm, and having access to a hot shower provided a significant morale boost. We left promptly at 1 a.m., ensuring the chain was lubricated and donning some partially dry clothes for the journey ahead.

Despite being awake for 36 hours and riding for 12, I could not sleep for a second night in a row. My eyes were closed and my mind was going at 1000kph. Could we make it? 300 kilometers was on tap for the next day with only a few hundred less meters of vertical ascent on tap for the day. It was hard to trust my body when I felt this wrecked and miserable. I knew the others felt just as awful.

Immediately the separation started and I cranked through the kilometers, surprisingly spry. The beginning was very rough farm roads, potholes strewn in every direction I pointed my wheel. There was no smooth sailing, and each kilometer grew increasingly annoying. I was anxious to get to the coast in time to see the sunrise. Climb after climb, the route flirted with the border of France, so close that I got a welcome text message on my phone. Cute. Eventually I came to one of the fastest descents on a perfect gravel road. The city lay ahead, curving and rising gracefully by the seaside. Just above the charming village hung a reddening gibbous moon. Today was shaping up to be just fine.

The route wound through the town following a pristine paved road all to myself at 4am. The climb out of town looked beastly on the elevation profile. One section rose 110 meters in a kilometer, an average 8% grade. Pavement ended at an empty parking lot for a trail, and I followed the punchy pitches to the singletrack at the top. After a few harsh pedal strokes my tire abruptly slipped and I got off to hike the bike. The trail was at 15% and stayed that way for the next 120 meters. I prayed that this wasn’t going to be an arduous hike a bike section on the backside. Upon reaching the summit, the first rays of sunlight began to illuminate the horizon, casting the sky in a breathtaking natural gradient.

I hiked for a bit on the way down, hopping onto the saddle when I felt comfortable in the light of the creeping dusk. The trail work was magnificent at times. Stone walls had built below the path as it wound around a deep ravine. Here is where I may die. At least I’m happy.

The day’s swiftest descent awaited on the opposite side of the peninsula, as I descended into the charming town of Port Lligat. Zooming down at an exhilarating 56kph (feeling like lightspeed after averaging 21kph) my eyes teared up in the cold morning and I found myself surrounded by a picturesque seaside village, its buildings adorned in pristine white. Amidst the beauty, a glimmer of hope emerged – perhaps there would be an early morning coffee shop open. Knowing Spain’s tendency for late starts, especially with coffee, I held onto my sliver hope. Yet, to my delight, serendipity smiled upon me: one establishment had just opened its doors at 6am.

I indulged in everything my eyes grazed upon—four plates filling up my small table, accompanied by a steaming, rich Americano. My solitary Scout message to my weary companions: Cadaques offers warm meals and coffee. Join me, take a seat.

With broad smiles on our faces, we replenish our energy—we had conquered the darkness, reached the sea. What once seemed impossible was now within our grasp, even with 200km (126 miles)/9 hours still ahead of us. Energized, we bid farewell to our cozy coffee haven, prepared to conquer the upcoming challenges of the next two inclines before embarking on a lengthy flat stretch out of the town of Roses.

Cade and I tackled the double elevation hump with relative ease, the roads offering just enough texture to keep the downhill exciting. Despite my initial caution on my narrower tires, I gradually loosened up my shoulders and hips and began to feel more adventurous. Descending on a narrow paved road into Roses was exhilarating, making it difficult to restrain ourselves. While a few unexpected vehicles lurked around the corners, each turn revealed increasingly magnificent views—a backdrop of the blue Mediterranean, white condominiums ascending Santa Rosa De Puig-Rom, and the distant, snow-capped Pyrenees. Pinch me, I am dreaming.

In the town of Roses we stop at a supermarket to repack supplies of “chako buns,” various pastries, and water. I tried to pet my fourth perro with no success. They eyed me with suspicion, as if they could detect the scent of American consumerism and cheap cheeseburgers emanating from me, and preferred not to engage. The lack of sleep would catch me off guard. I never hallucinated images, but my brain would see a shape and then lockjaw latch onto an idea. Many odd roadside lumps turned into ‘dogs’ and my mind would scramble back to home and my 14 year old puppy, Leia. This dog was real, though. I think.

Roses to Pals was flat, zooming through farmlands, linking dirt roads to pavement to bike paths. I dodged through a congested horse farm, the mares lingering on the bike path for attention. With the smell of fresh organic fertilizer in the air, I was grateful to have a cap for my bladder’s mouthpiece. Every 20km I would sneak into a village from what felt like a secret back entrance, ride through the plaza, and then head out in a matter of 90 seconds. It was a stark contrast from Unbound XL, where I relied on 180km intervals between each 24-hour Casey’s Gas Station. In Spain, the availability of services in these tiny villages posed another challenge, especially if it coincided with the afternoon siesta and then you’re screwed-esta.

The last daunting climb appeared on the elevation profile, ascending over 300 meters in 8km (5 miles/1,000 ft). Though not particularly sizable, some sections were incredibly steep, and my legs felt like lead after the past 20 hours of riding and lack of sleep. It took me 35 minutes, but it felt like it could’ve easily been two hours. Cade managed to bridge and then overtake me at the summit; the young guy was still going strong. With another 50k left to cover, I estimated at least a solid 2.5 hours of riding, even under favorable conditions. We began to intersect with other cyclists tackling various distances that day, and the course conditions deteriorated, becoming increasingly rutted and muddy. I pushed myself to the limit in the final stretch, longing to finish. Unable to consume any more calories and running on empty, finally returning to the road we had taken out of Girona felt like a tremendous relief—a return to the familiar.

I reached the vicinity of the finish line and leisurely paused my Wahoo, stepping off the course to await the arrival of my friends while checking their locations. It’s a peculiar feeling, concluding an epic event yet unable to officially cross the finish line. Nonetheless, we managed to gain entry to the food tent. Our conversation might have seemed disjointed to those who had recently completed the 360k, and while they appeared weary, we appeared downright disheveled. Our eyes were swollen, our attire stained with dirt, and we wore shell shocked masks.

Six out of fifteen individuals who embarked on the course successfully completed it, with four of them being our esteemed Rodeo team members. Our McDonald’s friend Zav pushed through the night and finished after 31 hours. After all the hubbub, Quinda Verhuel would take on the original 560km route that made its way through the Pyrenees over the course of 48 hours, an incredible feat. I take immense pride in our collective achievement amidst such a tumultuous week. After all, would we truly savor the warmth of the sun without enduring the rain? Risk is inherent in the pursuit of rewards. While the challenges may seem daunting in the moment, patience and perseverance invariably lead to triumph.

No comment yet, add your voice below!