Steve The Intern

Finding, Respecting, and Surpassing Limits. CB40 MTB Race

- ,

- , Races

This whole Trail Donkey project has been quite a romp, as I babbled on about in my last writeup on the subject. Now that we’ve ridden the spit out of the rigs, we have a fair amount of confidence in their abilities to convey us, under our own power, just about anywhere we point them. Beyond the typical dirt riding they’ve been seeing, Chris Magnotta notably rode his to 3rd place at the Deer Trail State Champ Road race here in Colorado. The only thing he changed from dirt spec to road spec was the tires. Chris is a bit of a monster rider anyway so we can’t go and say that a Donkey gave him magical powers, but we do think it is satisfying it’s original mission to be “one bike to rule them all”. We aren’t really kidding ourselves, we don’t think that a glorified cyclocross bike RULES other specialized road or mountain bikes in their respective disciplines, but it does road ride better than an MTB, and it does MTB better than a road bike, so we will be generous and playfully allow ourselves to keep using the title, tongue in cheek. Come at us, haters!

If the Trail Donkey makes a decent road bike and a decent trail bike, what might the limits of it’s abilities be? This was the question on my mind last week as the Crested Butte Fat Tire 40 mountain bike race quickly approached. A group of Rodeoers have had this race on the calendar since February and it had finally arrived. Crested Butte is, without a doubt, one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been. It lies five hours from Denver and even more hours from anywhere else. It’s remote location preserves it in it’s idyllic mountain setting, almost oblivious to the passage of time that the rest of the outside world must endure.

The mountain biking in Crested Butte is spectacular. They actually claim to have invented the sport there to some degree, but those sorts of claims are always disputed. What isn’t disputed is the quality of it’s trail network. Crested Butte easily has the most beautiful and scenic network of doubletrack and singletrack riding I’ve seen anywhere in the world. When I ride there I’m constantly stunned to the point of distraction by the scenery that waits around every bend. The scale of the mountains, the intensity of the colors, the spectrum of it’s wildflowers… Words really can’t describe it and photos will never do it justice. I’ll continue to use both here anyway.

The Crested Butte 40 is a race that has been ran for roughly thirty years, but this was my first attempt at it. Originally I assumed that I would just race it on my somewhat vintage but still capable YETI AS-R. The bike is over ten years old, but just last year still proved suitable enough to complete both the Leadville 50 and 100 MTB races. I have a fondness for the bike because we’ve endured a lot together, and I’m reluctant to retire her for a younger, faster model.

A lot has happened since I registered for the race though. Trail Donkey happened! After conquering most of the local trails around Denver on the bike, I started considering racing it in the CB40. This was, from the get go, a bad idea. I didn’t know what the CB40 course was like so it was impossible to know exactly how bad of an idea it was. That would need to be determined later! Filled with indecision, I loaded both of the bikes onto the old family Subaru, and, suspension collapsing under the load of a weekend’s worth of bicycular gear, we made the five hour drive to The Butte and into the unknown.

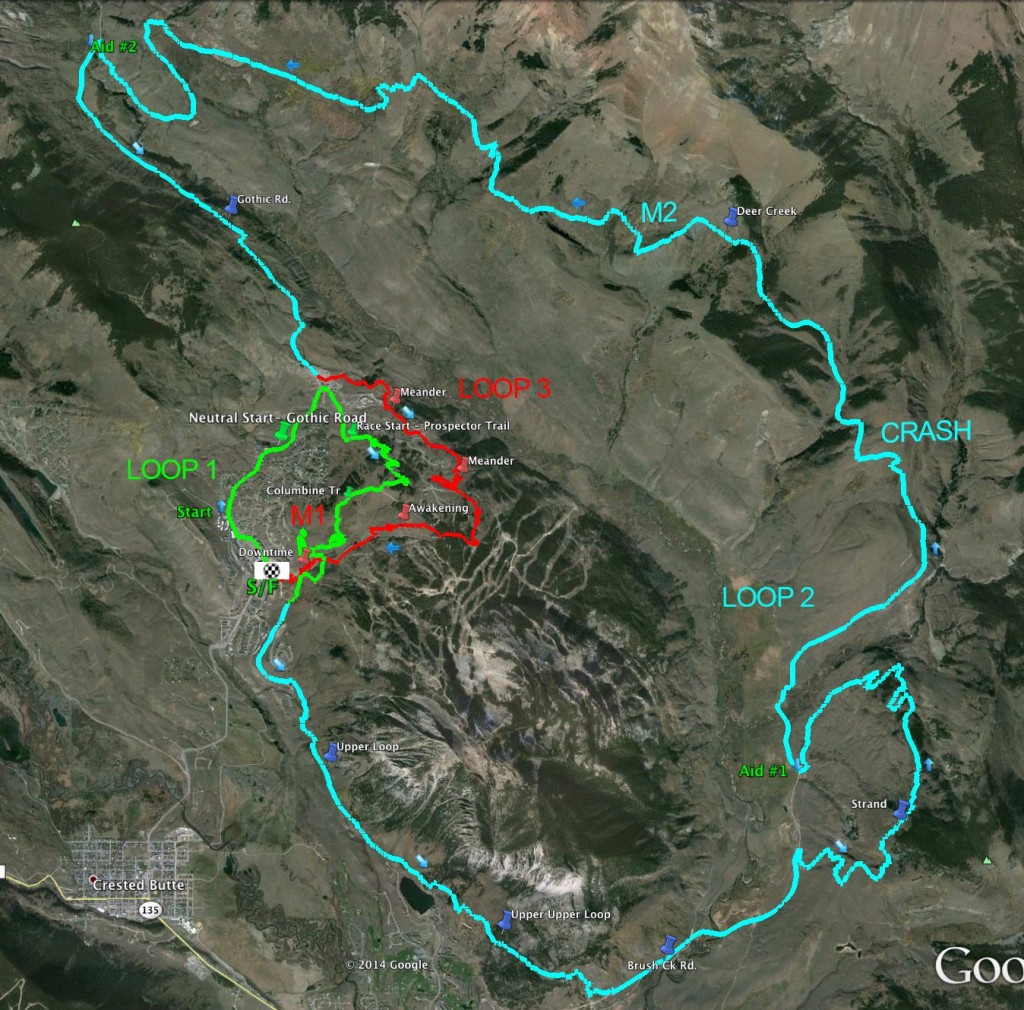

We arrived a day before the race and quickly set about planning some course scouting. Allow me to present a map:

The course originated at the base of the ski area, quickly climbed 1,000 feet, then bombed down a lovely descent (all in green) before beginning the larger 2nd loop (in blue) and culminated with another trip back up the ski area before again descending to the finish via a flowing trail through groves of aspen trees (in red). In all the course covered roughly forty miles and climbed about 6,000 feet, all at elevations beginning at approximately 9,000 feet. For a non-climber like me, this was all sobering news.

But what were the trail surfaces like? Were they too much for the fully rigid Trail Donkey on 42mm cyclocross tires? We needed to get out there and find out, so we took an evening spin on the first and third course loops to find out. What did I learn? I learned that the Trail Donkey was a very capable climbing bike, but a very limited descending bike. The loops that we rode were intermittently smooth and bumpy, but not SO bumpy that the Donkey couldn’t handle it. There was a clear disadvantage to being on a light duty off road bike though, especially on the descents where I watched Chris and Samer effortlessly drop me and put a few minutes into me each time the trail headed downwards. I was ok with this though. I knew I wasn’t going to win the race to begin with so losing some time on the descents in exchange for being able to challenge myself in a new way was worth the trade off. For me riding and racing bikes isn’t about winning everything. If it were I would hate the sport because I’m not that gifted of a rider and Colorado is STACKED with monster class riders and racers that can tear my legs off. Now days the novelty of a new challenge might be more rewarding than a win could ever be. So, with my two nominal scouting laps done and feeling reasonably assured that I could at least survive the race, I decided to pass over the Yeti and go with Trail Donkey for the race. But not before a quick pre-race bike wash:

Even if you aren’t going to win a race, I feel like it’s important to go to the starting line with an established goal. That goal could be to place in the top 10, or to finish under a certain time, or maybe just to survive. For me the goal of the race became to simply the answer the question “Can I do this? Can the bike do this?” and to hopefully come away from the event with my self respect intact.

On race day it was a novel thing rolling up to the starting line on the bike. Glances became double takes as people saw the number plate attached to the bike and realized that I intended to race it. Reactions ranged from “rad!” to “you’re crazy”. I quickly learned that, as far as anyone could remember, nobody had ever attempted the race on a cyclocross bike. That was a cool thing to learn: That I was, in one of the most bike crazy states out there, trying to accomplish something nobody else had tried. Of course, the fact that nobody had tried it because it was largely a stupid idea didn’t escape me. I had a bit of gallows humor about me as a lined up somehow at the very front of the starting group. All of these people behind me, I thought, were probably going to end up in front of me by the end of the race, and I would be “that guy” in their way out on the course! Yikes.

I quickly resolved to myself not to ruin anyone else’s day, and if I was caught by a faster rider, I would simply need to pull over and let them by immediately. Just because I was doing a little bike science experiment on my own didn’t mean everyone else had to suffer while I hogged the trail!

*pop!* The sounding gun sounded off, and the neutral roll out was underway. For the next mile as we rolled towards the trail head, everything was calm. The happy sound of knobby tires on pavement filled the air, and riders fell mostly silent as they braced themselves for the first big climb of the day. I took the time to simply reflect on the moment: Here I was, healthy and alive, up in the mountains, purely out playing in nature for the fun of it. I felt a sense of gratitude that I was even here at all. The world can be a nasty place, but in this place, surrounded by these mountains and these people recreating together, it didn’t seem bad at all.

And then we hit the singletrack. All sense of calm quickly turned into missed gear shifts, trail congestion, dust, and heavy breathing. Yeah! We were bike racing! Our pace quickened and we slowly headed skyward in a single line of riders weaving up the mountain. It was chaos! It was beautiful. I love this stuff! I was very nervous about this initial singletrack ascent. Strong riders would be game to get to the front and slower riders would be fading towards the back. On a road this would be no problem, but on a trail with no room to pass this could be a recipe for bike rage. Strangely, none materialized. Everyone quickly fell into a rhythm on the trail and most riders seemed content to proceed up the hill at whatever pace the single file line allowed. This even included me, on my Donkey! The bike rode great on that initial climb, and I was well under my limits keeping pace with the group that I was in. Sure, the leaders were pulling away further up slope, but I wasn’t racing against the leaders, I was only racing against myself and my own abilities. I felt great!

And then things got interesting. We crested the top of the first climb and quickly began a riotous descent down the ski area towards the beginning of the blue Loop 2 on the map. I had taken some video of parts of the descent while pre-riding the day before so… here it is:

As I cautiously descended things seemed to be going fairly well. Riding a fully rigid bike like the Donkey requires some pragmatism. One simply cannot descend as one would on a fully suspended mountain bike. One must go slower out of necessity. High speed amplifies the impact of rocks and bumps on both the equipment AND the rider. Without suspension to roll over obstacles, a large rock could easily mean a destroyed wheel or a tumble over the bars and down the mountain side. Putting caution into practice meant letting mountain bikers disappear down the trail in front of me and it meant keeping my ego and ambition in check. Instead I simply focused on the trail and reminded myself that I had forty miles to cover and that caution was an ally that would help me get there. Halfway down the first descent I had my first mechanical. The trail turned quite bumpy in the aspen grove, and a large blow caused by an aspen root caused my handlebars to slip down in the stem. This was scary! When I thought about a it a bit this was also not unexpected. I descend in the hoods and all of that weight out over the clamping point in the stem is a lot of leverage for those poor stem bolts to overcome. I brought the bike to a quick stop, pulled off the trail, and got to work re-adjusting and re-tightening the bars with my allen wrench. Riders sped by as I did, and I’ll admit that it was a huge bummer to watch them pass me so early in the race. Perhaps keeping my competitiveness in check was an impossible goal after all. I didn’t just want to survive the race, I wanted to try to surprise people with how well I could do.

Repairs complete I continued on my way and finished the descent without incidence. Nobody else passed me, and on a section of road and smooth singletrack called Upper Loop (on map above) I re-caught some of the guys who had passed me while I was pulled over. It became clear to me that when the terrain was smooth the Trail Donkey was a very very fast steed. The low rolling resistance of the Conti tires was one of the only mechanical advantages my bike had over the mountain bikes, and it made me slightly giddy every time I got to use that advantage.

Happiness was short lived as we exited Upper Loop and entered UPPER Upper Loop. Upper Upper Loop? Even though the names were similar, the two portions of trail could not have been more different. Where Upper Loop was smooth and fun, Upper Upper Loop was shockingly rocky, seemingly paved with the teeth of Satan himself. It was so damn rocky! My progress quickly slowed. I tried to pick careful lines and muscle the bike over the rocks, but once again my trail mates dropped me and disappeared into the forest in front of me. I was alone again, and I was afraid. I hadn’t pre ridden this part of the course, and I was not prepared for how difficult it was to ride on my chosen bike. I questioned my sanity and I questioned my odds of success. I abandoned hope of cleaning the trail and started shouldering the bike in a brisk jog whenever things looked overly challenging. Running with the bike is better than stalling, falling over, or pinch flatting. The roughly fifteen minutes I spent in Upper Upper were a low point of the race for me, but I pushed through it. The trail climbed through more groves of aspen and eventually began a rocky descent. It was here that I became very very thankful for the dropper post that we had put on the bike. I slammed it into the low position, put my weight way back, and more or less bobsledded my way down the mountain. I experienced the first of a lot of fear on the descent. I was only about 50% in control and instead of steering the bike I was mostly just trying to suggest that it should maybe go to the right or to the left instead of slamming into that rock or that gulley. I really, truly, honestly don’t know how I made it to the bottom of the hill and back onto the double track road, but when I did I was elated – filled with new hope that I would survive the day.

Have I mentioned how much Donkey loves a good double track gravel road? IT LOVES IT! I quickly put the bike into a good cruising gear and mashed the pedals in anger. Our speed quickly rose and it wasn’t long before once again I found myself catching guys I recognized from a half hour earlier, guys I thought I’d never see again. This was amazing! Trail Donkey couldn’t descend a bumpy trail very well, but all sins were forgiven on the gravel.

I settled in back with a group of guys as the gravel turned 180 degrees and started climbing the Strand trail. As we started climbing I heard them talking to each other:

“Yeah, I saw him pulled over on the side on the first descent. I don’t know what happened.”

“I lost him on Upper Upper.”

“I’ll bet he’s re-considering his bike selection right now.”

Whoa whoa whoa. Wait a minute. They were talking about me! Apparently they didn’t know I was right behind them. I decided to have some fun and chime in.

“Yeah, that guy is HURTING!” I said. “He is definitely having second thoughts right now.”

This was all true, by the way. I was hurting and I was having second thoughts about this whole crazy Donkey idea.

But then a funny thing happened. The road continued to be smooth and I felt better and better. I realized that I could be climbing faster. I gave the bike a little gas, pulled to the right, and went around the other riders.

“Steve!” some one shouted. It was my friend Samer! He was one of the guys talking and I hadn’t realized it. “Go go go man!” he shouted. We both smiled, and I pulled passed them into the lead. My Donkey advantage compounded on that climb and I caught and passed another six riders before reaching the top and once again entering a singletrack descent.

Oh what a descent it was! I could fill a paragraph with superlatives about pain, fear, panic, loss of control, muscle fatigue, numbness, and other descriptors. But to put it simply this was the point in the race where I realized that for the first time in my life I was in a race where I would look forward to the climbs and loathe the descents. Crested Butte’s trails are just not well suited to a rigid Trail Donkey. Some trails actually are, like the ones in Buffalo Creek. Those weave effortlessly and smoothly down the mountain. But Crested Butte has rocks, rocks, and aspen roots on almost every descent and these just absolutely pulverize an un sprung bike and it’s rider. As I descended Strand a new and unknown enemy showed it’s face: I was spending so much energy and muscle strength trying to control the bike on descents that I was quickly burning out my body only fifteen miles into the race. I could feel the familiar precursors to cramps coming on, and I knew I was in a heap of trouble if my muscles were starting to lock up this early into the event.

< Photo credit Trent Bona Photography

“Get smart Stephen!” I said to myself. I had to adapt my riding to the challenge even more. I had to slow down even more on the descents, let my body rest, and suck up the continued time losses. When I finally did re-emerge on the road at the bottom of the climb I was totally exhausted. Where other riders had rested a bit and cruised down the hill, I had completely fatigued myself to the point of exhaustion. I was thrilled to arrive at aid station #1, pause, eat some food, and refill my bottles. The cheers from the aid workers lifted my spirits and made me smile:

“Yeeeahhhh! Woooooo! Way to go! Looking good! WHAT THE HELL IS THAT A CYCLOCROSS BIKE!!!!”

We all laughed. With water bottles and food topped off, I got back to the work of racing my bike. Being that I was once again on a dirt road I quickly got back up to speed and set a tempo pace that allowed some recovery but also saw me once again catching all of my familiar wheel mates. This time we all smiled and laughed when we saw each other. We knew the drill. They’d drop me on the descents and I’d claw back on the climbs. As I distanced them near the top I told them I’d see them again shortly when they all dusted me on the next descent.

Speaking of dusting, the next descent is where I had my big crash of the race. I summited the climb and started following the wheel of another rider close in front of me. We started bombing down the road and the smooth surface disintegrated into a giant rut. As the rut got deeper and I continued down it I got a semi weightless off balance feeling. I knew I was going to go down. I kept rolling and my lean to the right got more and more severe until it was time to let go of the bars, reach for some soft looking bushes, and ditch the Donkey in the dust. When I came to a stop I looked around. No apparent blood, no torn clothes, but my handlebars were twisted to the side pretty badly. I was jacked up on adrenaline and instead of repairing the bars with a tool I just grabbed them and twisted violently until they straightened up. Problem solved! Back on my way, slower now, all of my wheel mates had disappeared and I found myself alone again descending ever slower, ever more cautiously.

“Just get through this” I thought to myself. “Don’t get hurt, don’t break the bike, DON’T DNF!”. A DNF would be horrible. I couldn’t bear the thought of it. I HAD to ride smarter.

The next ten or so miles were a huge blur. The Deer Trail climb was terribly brutal. For a while it was rideable and I re gained some time in the race, but eventually the effects of fatigue caught up with me and many other riders and we found ourselves pushing our bikes up exceedingly steep inclines. Maybe with fresh legs they could be ridden, but we were all entirely whooped and I think we took solace in the fact that everyone around us was walking. Every once in a while the trail would descend for a bit and I would get gapped again. Being increasingly tired and cautious the gaps got bigger, and I one by one lost track of many wheel mates for the rest of the race. I was dropped and I was exhausted.

To paint a picture of the exhaustion: I actually did try to eat to get some strength back, but I found it impossible to coordinate pedaling, steering, and chewing at the same time. I ended up with a large piece of Trail Nugget formed to the top of my mouth for about ten minutes until I finally stopped long enough to chew and swallow it. Later, on the brink of total dehydration, I hit a large bump and my water bottle ejected itself and tumbled down the mountain. I could only watch in disbelief.

“I’m completely effed.” I thought. I had to cover another hour of the course before I would arrive at the second aid station, and I had to do it without water.

Somehow I survived this hour. What got me through was the desperate desire to finish the race and to finish it with my self respect intact. Suffering is guaranteed in races, adversity is guaranteed, unexpected setbacks are exactly expected. This is in a large part why we do these sorts of things in the first place. We want to find challenges, find limits, and overcome them with a bit of courage and determination. If we do then the effort is immensely rewarding. If we give up then we are left with a failure that sticks with us in perpetuity. I had willingly entered a difficult race on the “wrong” bike, and now I was reaping what I’d sown. Even though in those moments I was fairly miserable, I also loved all of it. This is endurance sports. This is enduring. It’s beautiful stuff!

I made it to the second aid station, but not before stopping to repair a shift lever that worked it’s way loose on the washboard descent. Setbacks like that were now cause for a smile, they just made the story more interesting. My finishing time would just be a boring number, but the events on the trail were something to talk about later. Setbacks and mechanicals were the spice of the ride. Surprisingly, I didn’t even have it as bad as other riders did! Plenty of riders completely cramped and had to convulse in agony beside the trail for minutes on end. I passed a very strong rider carrying his bike with an impossibly destroyed front wheel. This sight of it made me thankful that somehow my beta Donkey wheels were still not only functional, but also completely true! Wonder of wonders!

After guzzling two water bottles and eating a bunch at the second aid station I set off on the beautiful, GLORIOUS gravel road from Gothic back down to the ski area. The road was pure ecstasy. The bike just flew down it with seemingly zero effort. I was re-hydrated, re-fueled, and re-w00ted. I only had to make it up one more 1,000 foot climb, down another 1,000 foot descent, and I’d be done with the race. Exhaustion was still present, cramps were still threatening, and my entire upper body was twice as fatigued as my lower body, but I could smell the scent of triumph. I knew I had this race in the bag and I felt like a million bucks. Onward!

The final climb was merciful in it’s gradient and I reeled in two riders along the way. Small goals like catching “just one more guy” do wonders for motivation in a race, so even though I was almost done I didn’t let off the pace. “Race through the finish” goes the saying. Keep your momentum up and never sit up and relax, even when you’ve all but finished.

I summited the final climb and pointed Trail Donkey down the hill towards the finish. There remained only about ten minutes of descending left, but it was mild descending compared to what I’d seen earlier in the race, and I can almost say I enjoyed it. I had taken a video of the finish descent the day before, and here it is:

As I neared the finish something surprising happened, I got a little bit overwhelmed. Some might call it emotional. What was this? What was happening? It hit me: This race had been hard. I’d done longer races many times, but never have I done a race like this where the course took such a massive physical and mental toll on me in such a short time. As I neared the finish I heard my name on the PA, I felt a sense of pride. Not a-hole pride where I think I’m better than anyone else, but the deep satisfaction sort of pride where your accomplishment was in peril and you snatched it back from the jaws of defeat more than a few times. I spotted my kids, hammered the last few pedal strokes, and crossed the finish line with a very enthusiastic hand in the air even though I was very much not the winner of the race.

Post race it was all relief. Exhaustion hit me like a truck once I knew I could stop fighting it.

When I started this race I thought I was entering an event where I would test the Donkey and continue to explore it’s limits as a bicycle and a concept. The more I rode on Saturday the more I realized that there is some validity to that, but bike races are always first and foremost a test of the pilot, the rider. Bikes don’t hurt, bikes don’t cramp, bikes don’t get discouraged. They do what they do directly in relation to the forces exerted onto them by the athlete. So while I am happy to say that Trail Donkey survived the Crested Butte Fat Tire 40, the bike itself contains no special magic. It’s a cyclocross bike with big tires, big gears, great brakes, fantastic wheels, and a dropper post. Those are the facts, and everything else is hype. I can get lost in the tech and gear side of the sport pretty easily, but the human side is WAY more interesting. We can test ourselves on almost any bike. Just today I saw a $20,000 bike announced, truly a work of engineering art. That bike won’t pedal itself though, neither did Trail Donkey, and neither did the bikes that finished the CB40 more than an hour quicker than I did. So two cheers for The Donkey, but three cheers to any rider who sets any sort of personal goal and accomplishes it on their own terms.

4 Comments

Great write-up! Where do you put your camera while filming?

I…umm… tend to just bite down on the tripod mount. Strange, yes, but it’s a great POV and surprisingly ergonomic.

Crazy idea. I have to try this :)

Awesome story. Came across this article because of my (maybe idiot) plan to replace my MTB and roadbike with one do-it-all bike, a cyclocross bike. Loved reading it, although i’m still not sure what to do.