Donkey Boy

Donkey Boy V. The RockStar Gravel Route

- ,

- , Adventures

For most of us, endurance lays on a glorious spectrum of absurdity; a hobby devoted to journeys and dedicated to adventure.

For my family, the spectrum of endurance is firmly screwed. Thanks to my ultra-running dad, Andy Jones-Wilkins, our family vacations seemed to always veer deep into the mountains of some Western state and included some 20-odd hours zig zagging rental cars over terrain they should not see. We would hustle to prepare food, bottles and gear that were the fuel to my dad’s many endurance endeavors, while forging our familial bond trough the peripheral wild spaces. It sure beat summer camp, if you ask me.

Sometimes I would get to join my dad, at the end of these runs, to pace the last five to fifteen miles. These miles were often lethargic, frequently ambulatory, and always ~grumpy~, yet these are the moments I have had with my father that mean the most. They defined him, in my own mind, as strong, resilient and great.

What I saw from those dark nights slogging down trails at the end of his hundred-mile days was the best of him in the moments where he was at his worst. They were moments of pure endurance that lured me into to his passion to his personality, that I desperately wanted to capture in my own life.

In total, my dad has run forty hundred mile running races. I haven’t been to all of them, but I like to think I have been to the important ones. I have seen him win, top-ten and even struggle to finish. But, through it all, both from the aid stations and on the trail, I saw a relentless love for the task at hand and a model for finding a deep happiness. I wanted it, I approached it, but I never found it.

As I grew up and began gravitating towards endurance sports, that disconnect was hard to shake. Running wasn’t for me and road cycling wasn’t for him. Too many pesky tactics, mechanicals and excuses.

No, for my dad cycling was endurance light; endurance on the surface, but a sport that lacked the grinta of a true expression of endurance. While he always supported me, he was like me as a paced him through the night: a sympathetic spectator. We were training, eating, and living the same way, yet operating in fields that were inescapably separate.

So, a month ago as Ryan and I formulated our plan to take on the Rockstar “ultra” gravel route, I knew it had to be a family affair. Separated from the pitfalls and perceived shallowness of the road circuit, we could share an endurance journey that his ultra-tinted glasses could distill and digest, while also seeing if the traits I found in him could be reflected in my effort.

Let’s call it meeting in the middle.

Alas, this is not just a story about me and my dad. We just aren’t that cliché. Endurance is a family affair, and I’d be damned if I left out the star of the show, la jefe: Shelly Jones-Wilkins.

While my dad may have been that picture of resilience, the artist behind that picture was without question my mom; guiding, prepping and talking Andy through the many runs that defined his life. In fact, if it was not for my mom’s athletic aptitude and undying endurance exploits of her own, Andy would still be the 200-pound frat tzar who my mom met in Philadelphia.

While he tends to reap the rewards, it was Shelly who sewed the seed.

Unlike my dad, Shelly found cycling to be the perfect avenue to guide me through my athletic education. Learning as I did the interworking’s of junior racing, strategy and teamwork, Shelly and I raced our way through countless weekends strewn across the country chasing dreams and lessons. It was so natural, yet also so disruptive. With the dad I had and the boys club that cycling often is, the fact that my mom was the one – all five-foot, zero-inches of her– bullying her way to the good spots in the feed zone, seemed to be gleefully unique.

While Rockstar may have been a new way for me and my dad to connect our endurance journeys, it was very much the next logical step in my mom and my progression. In an endeavor that seemed absurdly nascent, I knew she would be the grounding. She was the link that would tether my ride to the experiences I knew, and she would continue to be the sports phycologist who always knew what to say.

Between the two of them and Tully, my absolute rock of a little brother, the crew was set. It was two decades and two generations in the making – full of different skills and outlooks – all scared and excited in their own little ways.

Truly the most glorious ingredients for a gangbusters Easter weekend.

Armed with an ultra-crew (in every sense of the word) I started the ride under something of a false sense of comfort. The weight of the day was ever so lifted from Ryan and my shoulders; just enough to get the wheels churning at 4:15 a.m. with just the slightest bit of security. Security that quick became a necessity.

While Virginia is normally removed from the tentacles of frost, snow and sleet by April, this go-around old man winter made a final lunge at the Blue Ridge on the weekend of our attempt. Instead of the forty or fifty degrees that we had envisioned, we had to navigate a morning where the mercury huddled around 20 degrees, with the possibility of snow high on the first ridge all too real.

Yet, being the intrepid riders we are, we set off down the moonlit road with the aplomb of a jovial pig on their ride to the slaughterhouse; our doom approaching as we feigned stoke. 250-miles of insanity was enough of a challenge that any additional adversity seemed like gravy. The cold was just another layer to the thick-a** dip we were about to be stuck in.

That is, until I nearly drowned in it.

Not even two hours later, the sky still black and the air still frozen, I stood in a creek with wet gloves, feet, legs and jacket contemplating the stupidity I found myself in. In a stroke of Icarus genius, I had tried to clear a near frozen creek with a 400-lumen light as my guide. Needless to say, that trip across the water ended with my Donkey graciously catapulting me deep into the dark current bellow.

Although I emerged from the river wet, the real element that soiled my body was a deep and insidious fear. Fear of the slaughterhouse that was up on the ridge, invisible in front of me. A slaughterhouse not filled with tangible devices of death, but instead a silent consuming agent of nature that is every outdoorsman’s nightmare. Yet, in the face of that fear, the solution remained shockingly simple.

Just keep moving.

Looking back upon those next couple hours is an interesting challenge. Perspective is tricky like that. Scratch that. Time is tricky like that. While during the hours that followed time crawled by, I sit here in my warm desk reflecting on the day and that time is just the briefest moment of the mental movie, yet its impact reverberated throughout the whole day. It played out in slow motion in my mind, yet really it only tinted the entire portrait.

Coincidentally, those moments of extreme cold were also objectively moments of supreme beauty. With the sun came color to vividly wash the landscape in an attitude that was so contradictory to the feeling that I know I felt. It is almost impossible for me to look back at those hours at anything approaching a realistic sentiment. Its almost as if I am sympathetic to my former self, but I lack the understanding to see my former self with empathy.

The hurt was a part of something so epic, so grand, so utterly spectacular, I can’t remove the feelings and love for whatever happened after. Maybe that’s what makes endurance as captivating as it is. In the wild grandness of true endurance exploits, the inescapable moments of darkness get lost, illuminated, and colored with the inevitable high notes. It’s a natural mediation of zen, flow, grace and chaos that combine to produce days that are the fleeting moments of transformation everyone wants to find.

Moments that shaped my dad into the figure that inspired my own quest for my own long path less taken.

Moving past Rockstar and onto other events and challenges will tell the full story of the impact the day had on me. In fact, it may take until I have a child of my own seeing the fire in my eyes for me to truly grasp the levity of what Ryan and I just finished. All I can really say now is how happy I am to have taken on the challenge, how happy I was to find these new limits in my own state, in front of my own family and on my own terms.

Lastly, I am happy for the cold. I am happy for the river. I am happy, because they showed me how even in the worst of times, a day can be salvaged by just a little perseverance. With that knowledge, what could stop me?

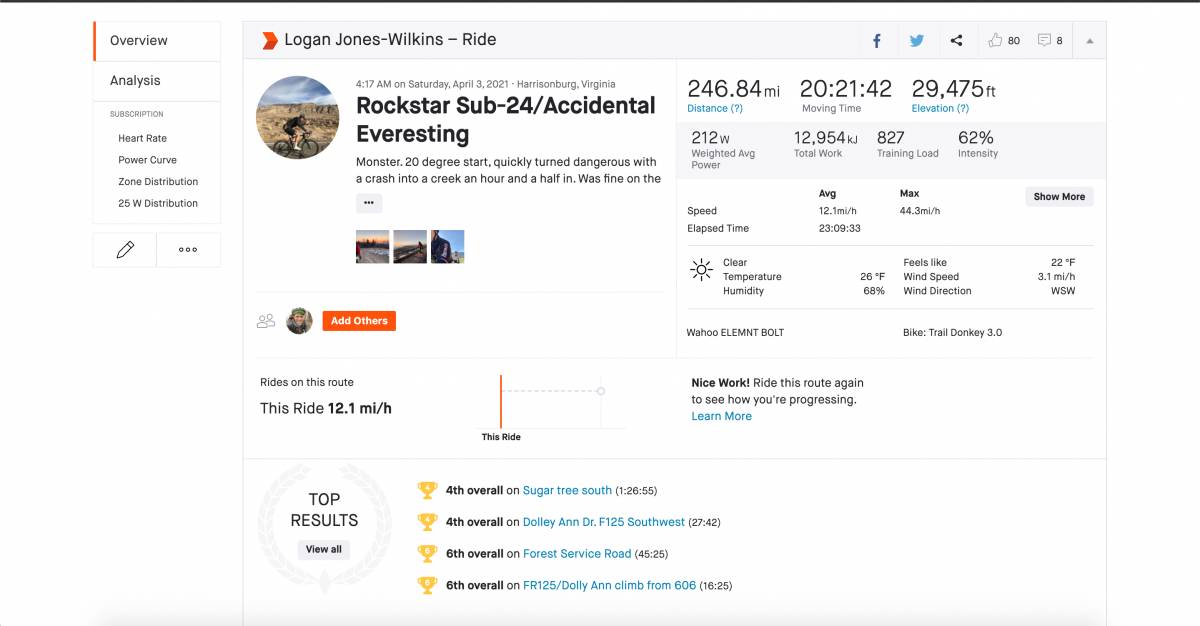

Here is the link to see the ride details on STRAVA, and here is the link to website if you would like to try RockStar for yourself!

No comment yet, add your voice below!